Wave activity on Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, may be strong enough to erode the coastlines of lakes and seas

MIT, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution researchers find wave activity on Saturn’s largest moon may be strong enough to erode the coastlines of lakes and seas.

Woods Hole, Mass. -- Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is the only other planetary body in the solar system that currently hosts active rivers, lakes, and seas. These otherworldly river systems are thought to be filled with liquid methane and ethane that flows into wide lakes and seas, some as large as the Great Lakes on Earth.

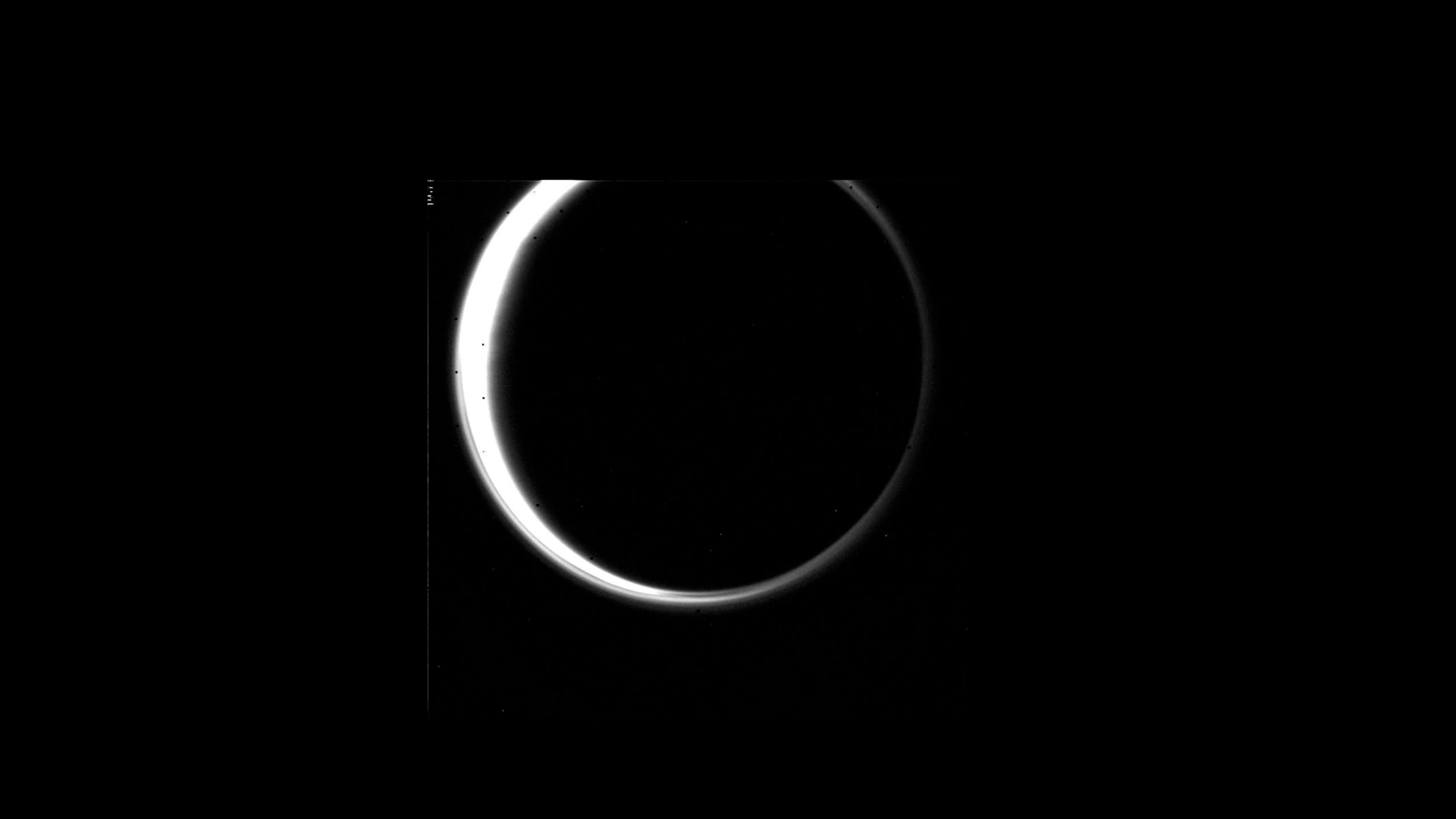

The existence of Titan’s large seas and smaller lakes was confirmed in 2007, with images taken by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Since then, scientists have pored over those and other images for clues to the moon’s mysterious liquid environment.

Now, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and MIT geologists have studied Titan’s shorelines and shown through simulations that the moon’s large seas have likely been shaped by waves. Until now, scientists have found indirect and conflicting signs of wave activity, based on remote images of Titan’s surface.

WHOI’s Andrew Ashton, associate scientist in Geology & Geophysics, is a co-author on the study, “Signatures of wave erosion in Titan’s coasts,” published in the journal Science Advances.

Rose Palermo, a former MIT-WHOI Joint Program graduate student and a research geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey, is first author on the study. Additional co-authors include MIT research scientist Jason Soderblom, former MIT postdoc Sam Birch, now an assistant professor at Brown University, and Alexander Hayes of Cornell University. Palermo was co-advised by Ashton and Taylor Perron, the Cecil and Ida Green Professor of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences at MIT.

The team took a different approach to investigate the presence of waves on Titan, by first modeling the ways in which a lake can erode on Earth. They then applied their modeling to Titan’s seas to determine what form of erosion could have produced the shorelines in Cassini’s images. Waves, they found, were the most likely explanation.

The researchers emphasize that their results are not definitive; to confirm that there are waves on Titan will require direct observations of wave activity on the moon’s surface.

“We know that, even on Earth, different processes create different shoreline shapes. Quantifying the difference between these shapes, however, has remained a challenge,” said WHOI’s Ashton. “We can say, based on our results, that if the coastlines of Titan’s seas have eroded, waves are the most likely culprit,” said Perron. “If we could stand at the edge of one of Titan’s seas, we might see waves of liquid methane and ethane lapping on the shore and crashing on the coasts during storms. And they would be capable of eroding the material that the coast is made of.”

Taking a different tack

The presence of waves on Titan has been a somewhat controversial topic ever since Cassini spotted bodies of liquid on the moon’s surface.

“Some people who tried to see evidence for waves didn’t see any, and said, ‘These seas are mirror-smooth,’” Palermo stated. “Others said they did see some roughness on the liquid surface but weren’t sure if waves caused it.”

Knowing whether Titan’s seas host wave activity could give scientists information about the moon’s climate, such as the strength of the winds that could whip up such waves. Wave information could also help scientists predict how the shape of Titan’s seas might evolve over time.

Rather than look for direct signs of wave-like features in images of Titan, Perron noted the team had to “take a different tack, and see, just by looking at the shape of the shoreline, if we could tell what’s been eroding the coasts.”

Titan’s seas are thought to have formed as rising levels of liquid flooded a landscape crisscrossed by river valleys. The researchers zeroed in on three scenarios for what could have happened next: no coastal erosion; erosion driven by waves; and “uniform erosion,” driven either by “dissolution,” in which liquid passively dissolves a coast’s material, or a mechanism in which the coast gradually sloughs off under its own weight.

The researchers simulated how various shoreline shapes would evolve under each of the three scenarios. To simulate wave-driven erosion, they took into account a variable known as “fetch,” which describes the physical distance from one point on a shoreline to the opposite side of a lake or sea.

“Wave erosion is driven by the height and angle of the wave,” Palermo explained. “We used fetch to approximate wave height because the bigger the fetch, the longer the distance over which wind can blow and waves can grow.”

To test how shoreline shapes would differ between the three scenarios, the researchers started with a simulated sea with flooded river valleys around its edges. For wave-driven erosion, they calculated the fetch distance from every single point along the shoreline to every other point, and converted these distances to wave heights. Then, they ran their simulation to see how waves would erode the starting shoreline over time. They compared this to how the same shoreline would evolve under erosion driven by uniform erosion. The team repeated this comparative modeling for hundreds of different starting shoreline shapes.

They found that the end shapes were very different depending on the underlying mechanism. Most notably, uniform erosion produced inflated shorelines that widened evenly all around, even in the flooded river valleys, whereas wave erosion mainly smoothed the parts of the shorelines exposed to long fetch distances, leaving the flooded valleys narrow and rough.

“Once we had fetch happening, we were able to see differences in how shoreline shape evolves, said Ashton.

“We had the same starting shorelines, and we saw that you get a really different final shape under uniform erosion versus wave erosion,” Perron said. “They all kind of look like the flying spaghetti monster because of the flooded river valleys, but the two types of erosion produce very different endpoints.”

The team checked their results by comparing their simulations to actual lakes on Earth. They found the same difference in shape between Earth lakes known to have been eroded by waves and lakes affected by uniform erosion, such as dissolving limestone.

A shore’s shape

Their modeling revealed clear, characteristic shoreline shapes, depending on the mechanism by which they evolved. The team then wondered: Where would Titan’s shorelines fit, within these characteristic shapes?

In particular, they focused on four of Titan’s largest, most well-mapped seas: Kraken Mare, which is comparable in size to the Caspian Sea; Ligeia Mare, which is larger than Lake Superior; Punga Mare, which is longer than Lake Victoria; and Ontario Lacus, which is about 20 percent the size of its terrestrial namesake.

The team mapped the shorelines of each Titan sea using Cassini’s radar images, and then applied their modeling to each of the sea’s shorelines to see which erosion mechanism best explained their shape. They found that all four seas fit solidly in the wave-driven erosion model, meaning that waves produced shorelines that most closely resembled Titan’s four seas.

“We found that if the coastlines have eroded, their shapes are more consistent with erosion by waves than by uniform erosion or no erosion at all,” Perron said.

The researchers are working to determine how strong Titan’s winds must be in order to stir up waves that could repeatedly chip away at the coasts. They also hope to decipher, from the shape of Titan’s shorelines, from which directions the wind is predominantly blowing.

“Titan presents this case of a completely untouched system,” Palermo said. “It could help us learn more fundamental things about how coasts erode without the influence of people, and maybe that can help us better manage our coastlines on Earth in the future.”

This work was supported in part by NASA, the National Science Foundation, the USGS, and the Heising-Simons Foundation.

Reprinted with permission of MIT News*

###

About Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate an understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment. WHOI’s pioneering discoveries stem from an ideal combination of science and engineering—one that has made it one of the most trusted and technically advanced leaders in basic and applied ocean research and exploration anywhere. WHOI is known for its multidisciplinary approach, superior ship operations, and unparalleled deep-sea robotics capabilities. We play a leading role in ocean observation and operate the most extensive suite of data-gathering platforms in the world. Top scientists, engineers, and students collaborate on more than 800 concurrent projects worldwide—both above and below the waves—pushing the boundaries of knowledge and possibility. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu.