In the Ocean Twilight Zone, Life Remains a Mystery

A New, Long-term Observation Network Could Help Reveal Its Secrets

This article printed in Oceanus Spring 2021

This article printed in Oceanus Spring 2021

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

LIFE IN THE OCEAN'S TWILIGHT ZONE HAS LONG FASCINATED SCIENTISTS. This vast, shadowy swath of water hundreds of feet below the surface is home to animals that defy imagination, from tiny, glowing fish with gaping jaws and needlelike teeth to gelatinous giants longer than the largest whale.

But even though there are gigatons of fish in the twilight zone, surprisingly little is known about them. Spread out across immense distances or clustered in isolated hot spots, they confound efforts to sample, image, or measure their abundance.

That could soon change.

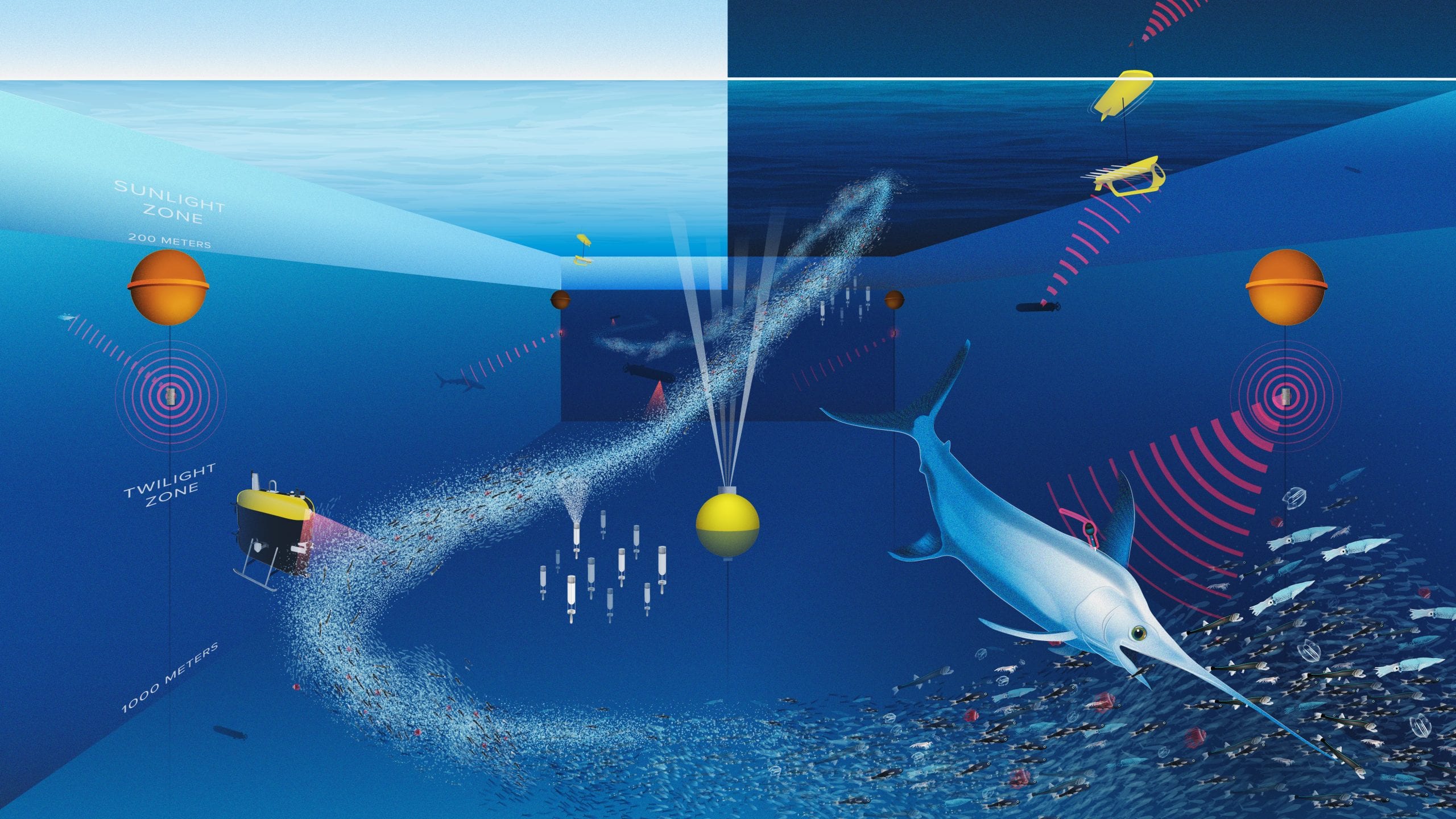

WHOI scientists are building the first long-term observation network focused on life in the twilight zone. Located in the Atlantic Ocean off the U.S. East Coast-out beyond the continental shelf, where water depths are measured in miles, not feet-the network will provide an around-the-clock view of life in the twilight zone over an area spanning close to one million square kilometers (~400,000 square miles).

Above: A free-swimming sea snail known as a sea angel flaps its winglike arms gracefully while in search of food, while another species (Diacria trispinosa, below) propels itself through the Ocean Twilight Zone with its tiny feet. (Photo by Paul Caiger, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

"This is really the first time that anyone has developed a system capable of collecting data with that kind of spatial and temporal resolution, specifically in the ocean's midwater," says WHOI ocean ecologist Simon Thorrold, who is helping to create the network. "It's going to be a huge advance."

Sound sources anchored at the network's four corners will send out acoustic signals that can be "heard" by tiny receivers in tags attached to bigeye tuna and swordfish, two commercially important species known to dive into the twilight zone for prey. By recording how long it takes sound from different sources to reach the fish, the tags can track their location in three dimensions. And, they work underwater, where GPS can't.

"Then after a year or so, the tag pops off the fish and floats to the surface, and all those geolocation data are relayed back to us by satellite," Thorrold says.

Another major component of the network-a central mooring equipped with active sonars-will complement the predator tracking data with information about the location and abundance of their prey: the small fish found in huge numbers throughout the twilight zone.

That mooring is being developed by WHOI acoustic oceanographer Andone Lavery, who is particularly interested in what its sonar will reveal about the largest migration on the planet-the nightly journey of twilight zone species to and from the surface to feed. Their movements fast-track atmospheric carbon from surface waters to the deep ocean, helping to regulate global climate.

"This is the perfect opportunity to do a long-term test of our new technology," Omand says. "We could put the MINIONS out for six months, or even up to a year. It will really advance our understanding of their capabilities to track carbon through the twilight zone."

“I’m thrilled that with a relatively small amount of funding, we can start to answer questions that may be vital to changing how we live.”

—Otto Happel, Happel Foundation

"We're hoping to get a much better understanding of the migration and how it changes over time-with the seasons, with water temperature, and with the currents," Lavery says. "What happens when you're in or out of the Gulf Stream? Does it impact the biomass of organisms that are migrating? Does it impact their speed? All of these questions are important to the carbon cycle."

At only a few inches in length, the black dragonfish (Idiacanthidae) is still a ferocious predator in the Ocean Twilight Zone, using its dangling lure and ensnaring teeth to trap prey looming in the dimly lit water. (Photo by Paul Caiger, © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution).

University of Rhode Island physical oceanographer Melissa Omand will be taking an even closer look at carbon in the twilight zone-through the cameras of small floating robots known as MINIONS. Each MINION will be equipped with the same novel tracking technology as Thorrold's fish, recording its position as it images carbon-rich particles sinking to deeper waters. Working with WHOI marine chemist Ken Buesseler, Omand plans to deploy a fleet of 20 MINIONS in the network.

Former WHOI President and Director Mark Abbott says it would be challenging to fund such a large-scale, long-term observation network through federal sources. Abbott helped champion the project during his tenure, enlisting the help of German philanthropist Otto Happel, whose interest in WHOI's twilight zone research led to a generous gift from the Happel Foundation.

"I think what's really exciting about Otto is his deep appreciation, understanding, and curiosity about the science, the engineering-and how they inform ocean policy," Abbott says. "He's concerned about all the changes we're seeing in the marine environment, and he wants to fund work that enables people to make better decisions about the ocean."

"The ocean always has been my passion, in many respects," Happel says. "It's of enormous importance for our future, and the future of our world. I'm thrilled that with a relatively small amount of funding, we can start to answer questions about it that may be vital to changing how we live."

With the Happel Foundation's support, the team plans to deploy the twilight zone observation network's first moorings this summer.