WHOI CSI Lab Investigates Rare Whales

Computerized Scanning and Imaging lab gets unusual double case

On a wintry Sunday morning in early January, a jogger came across what appeared to be a dolphin in shallow water, on a beach in Long Island, N.Y. He phoned the Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation, setting in motion a chain reaction that eventually led to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

Kimberly Durham, Riverhead’s rescue program director, mobilized her team, which responds to marine mammal strandings. On the way to the beach, she received cell phone photos and saw that it was no dolphin, but a rare, 14-foot adult female whale—a species called a True’s beaked whale. And there would be no rescue, because the whale had died.

“The necropsy (animal autopsy) could be done just by us,” said Durham, “but in a stranding, it’s important to touch all bases, especially with a rare animal, and such a fresh animal, and pull in every expert you have, to glean as much information as possible.”

From the beach, she called biologist Michael Moore, director of the Marine Mammal Center at WHOI and a specialist in forensic investigations of marine mammal deaths. Moore immediately suggested she call WHOI scientist Darlene Ketten to examine the whale’s head.

Headhunters

Ketten gets inside marine mammal heads—literally. A global expert on the ear anatomy and hearing abilities of marine mammals, she also uses forensic techniques and a CT scanner to investigate animal deaths.

Ketten has studied more than 100 species, but never before this a True’s beaked whale. Excited, she called her WHOI colleague, researcher Scott Cramer, to get a truck. “We’re heading off to get a head!”

These deep-diving whales live in the North Atlantic, seldom surfacing, and are rarely sighted alive or stranded on shore. Here was a chance to try to find not only what had killed it, but also to learn the most basic things about the anatomy of a rare animal in good condition.

Then, within a few hours, a second, smaller, very young male True’s beaked whale calf, likely the female’s offspring, was reported washed ashore nearby.

“We told WHOI, ‘Be prepared for two heads,’” said Durham. Cramer drove from Woods Hole to Long Island to collect them.

“My primary mandate is to try to find out why the animals died,” said Ketten. “But I also want to learn all I can about the anatomy of this species from cases like this.

“I see myself as an advocate for each individual I examine. Part of my obligation, even if I’m primarily interested in how they hear, is to look at everything the animal has to tell me—to look at the ears, but also to learn as much as I can from the body about the animal. We don’t have health records of these animals. But the body and the head is a record, of its life.”

CT scans and dissections

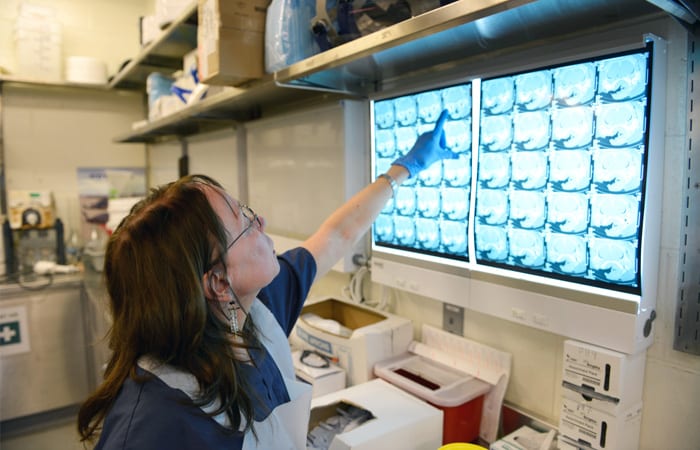

Ketten oversees the Computerized Scanning and Imaging (CSI) lab at WHOI, which houses a CT scanner that generates images of animals’ internal structure. The CSI lab serves researchers the world over, and has scanned a wide range of specimens beyond marine mammals, including coral, shrimp, squid, sharks, tigers, bats, elephants, and hippos.

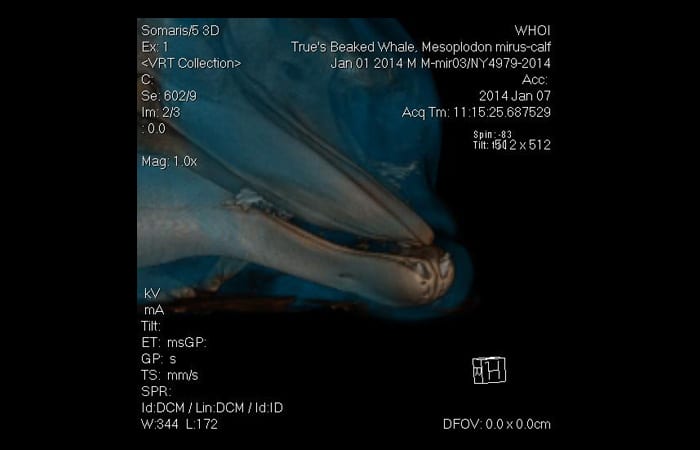

Ketten and the CSI staff imaged the heads of the two True’s beaked whales using the CT scanner. The scans showed the heads’ anatomy in a series of 2-dimensional slices and rotating 3-dimensional images.

Then Ketten performed physical dissections of the whales’ heads in WHOI’s specialized necropsy facility, looking for evidence of trauma or disease.

CT images on the light boards near the dissecting table in the necropsy lab helped guide the exam. The earbones, or bullae, appeared bright white in the scans. They are the densest bones in the whales’ bodies, which helps the ears withstand the pressure of the deep ocean.

“This is the delicate part,” Ketten joked, using a chisel and hammer to expose the extremely dense ear bones, which are shielded by large flanges of the skull behind the lower jaw.

“Sometimes the scans show us right away some clear evidence of an illness or trauma; we see a brain tumor, an infection, a healed scar or wound,” said Ketten. “But with these animals, there is no obvious pathology. What we do have is some really great new data on the head anatomy of this species, both at an adult and juvenile state. Really a unique set of cases.”

She extracted samples of the whales’ fats and ears to add to an extensive database of marine mammal auditory anatomy. In a collaborative project on whale hearing, two True’s beaked whale ears were sent to Boston University where researchers will take precise biomechanical measurements of ear membrane stiffness, which is related to hearing capability.

Answers to come

Meanwhile, separate necropsies on the whales’ bodies were underway at Riverhead. “But I don’t want to know their findings before I examine the heads,” Ketten said, “because it could prejudice what I see.” After the investigations they will share their reports to put the whole picture together.

The Riverhead researchers found that the female whale had little body fat and was lactating, and that there was milk in the juvenile male’s esophagus. DNA tests will confirm whether the whales are a mother-calf pair.

“It does appear that there was no obvious human involvement in the whales’ deaths,” Durham said. “We didn’t see evidence of trauma or plastic in the stomach, anything like that. The deaths were probably a natural event.”

The investigation continues. Ketten took samples of both whales’ brains to be examined for any infectious agent. Tissue samples were sent to a laboratory at the University of California, Davis, to determine whether the whales had contracted morbilivirus, a highly contagious cetacean virus. The virus, which does not affect people, caused nearly 800 dolphin deaths in 2013.

The Riverhead Foundation is the New York node of the Northeast Regional Marine Mammal Stranding Network, overseen by the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service’s Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program, which coordinates stranding networks, investigations of marine mammal deaths, and tissue analysis.

Slideshow

Slideshow

Rarely seen alive or dead, a True’s beaked whale was found dead on a Long Island beach on Jan. 5, 2014. Soon after this 14-foot-long adult female was found, the body of a juvenile True's beaked whale, likely the adult’s calf, was found on the beach. The Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation took charge of the cases and contacted biologist Darlene Ketten at WHOI to examine the heads and ears, while Riverhead examined the bodies. (Photo courtesy of Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation)

Rarely seen alive or dead, a True’s beaked whale was found dead on a Long Island beach on Jan. 5, 2014. Soon after this 14-foot-long adult female was found, the body of a juvenile True's beaked whale, likely the adult’s calf, was found on the beach. The Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation took charge of the cases and contacted biologist Darlene Ketten at WHOI to examine the heads and ears, while Riverhead examined the bodies. (Photo courtesy of Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation)- The heads of two True’s beaked whale were transported to WHOI’s Computerized Scanning and Imaging facility, where biologist Darlene Ketten and CT technologist Julie Arruda scanned them. Scientists from around the world use this scanner for research on marine mammals and animals ranging from shrimp to elephants. (Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI's CT scanner generates images of animals' internal structure, showing denser tissues in lighter grays and less-dense tissues in darker grays. In this cross-section image of a True's beaked whale head, the earbones, the densest bones in its body, show up as bright white. (Courtesy of Darlene Ketten, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Computerized Scanning and Imaging lab)

- A color 3-D CT scan of the head of a male calf True’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon mirus) reveals a characteristic of this species—tusks. In the adult female whale, the tusks were embedded in the jaw. But in the very young male calf, the tusks—the triangular projections at the tip of the jaw—had already erupted. (Courtesy of Darlene Ketten, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Computerized Scanning and Imaging lab)

- Kimberly Durham, director of rescue programs at the Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation on Long Island, during the rescue of a dolphin in 2013. (Photo courtesy of Riverhead Foundation for Marine Research and Preservation)

Related Articles

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- How to See What Whales Hear Oceanus story by Darlene Ketten

- The WHOI Marine Mammal Center

- The WHOI Computerized Scanning and Imaging Center