Of Sons and Ships and Science Cruises

A conversation with Capt. A.D. Colburn of the research vessel Atlantis

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has had an unbroken line of three ships named Atlantis that date to the Institution’s founding in the early 1930s. Arthur D. Colburn III, better known as A.D., who was recently named master of the modern-day Atlantis, is continuing another tradition: His father, Arthur D. Colburn Jr. (Dick), was the last captain of the first Atlantis. A.D. himself spent 13 years as a mate on Atlantis II when the procedures for diving the submersible Alvin from a large research vessel were first being developed. Then he took the helm of R/V Knorr from 1995 until early this year. A.D. and Dick are two of many mariners who have worked their way up on WHOI ships, devoting their careers to the success of the Institution’s seagoing operations.

Is there a seagoing tradition in your blood?

Yes, and also a WHOI tradition. My father’s career, of course, was my most immediate influence. I have vivid memories of the crew of Atlantis stopping by the house. As a little kid in pajamas, I picked up on the camaraderie and mutual respect. It was obvious they were doing something they all liked, and they were pretty proud of it.

My mother’s father, David Atwood, spent his professional life sailing for commercial enterprises. During family summers in Maine, we were always on the water. My mother also worked from 1945 to 1957 for geophysicist Brackett Hirsey at WHOI, where she met and married my Dad.

My wife Karen’s family also has a maritime history, and she and several relatives have worked on the Institution switchboard. Her father Buddy Baker was supervisor in the WHOI carpenter shop. So she knew what she was getting into with me!

When did you make your first WHOI cruise?

I must have been about six or seven years old—my Dad took me along on the last Atlantis shipyard transit. A couple of years later, he took the helm of WHOI’s small coastal vessel Asterias to spend more time at home with the family. Once when a WHOI scientist needed the boat in Casco Bay, Maine, but couldn’t afford to pay for its transit, Dad bought the fuel and took my brother, my grandfather, and me along—Woods Hole to Somme Sound, Mt. Desert Island, with fog all the way. Mom and my grandmother drove up to collect the rest of us while Dad carried on with the science program.

A decade later, I was a cadet at the Massachusetts Maritime Academy in Buzzards Bay. Dick Edwards, who was then WHOI Marine Superintendent, arranged for me to fulfill part of my required “sea term” aboard Knorr. Capt. Emerson Hiller was a good mentor, and little did I know that I would one day be sitting in his chair.

Was that your goal when you were a cadet?

I thought I would follow the path of my Atwood grandfather, who graduated from Mass Maritime in 1920 and went on to commercial ship work. I tried it for a while, but the shipping industry was in a downturn at the time. So I would return to work on WHOI ships.

One summer, I faced a decision: Work for the Steamship Authority in Woods Hole parking cars on ferries or relieve as a second mate on Knorr. I went deep sea, and I’ve never regretted it.

Tell us about a memorable cruise?

To the Labrador Sea in 1997, with Bob Pickart as chief scientist. Our goal was to measure the sinking of cold, dense water in the Labrador Sea—a phenomenon that drives world ocean circulation and one that requires true winter weather. A lot of people thought the obstacles—the ice, the cold, the stormy weather—would be insurmountable and predicted the cruise would not turn out well. I came to it with more confidence because early in my career I had some experience working in the Labrador Sea for an oil company.

It was a very tough cruise, but we just worked at it real hard. We focused on the safety of the people aboard first and also keeping the ship out of harm’s way. There was a constant watch for dangerous ice. We spent many hours chipping ice off the ship’s superstructure with the wooden mallets we brought along for that purpose, with crew members clipped into safety lines on icy decks.

The ship and crew performed extremely well in some really nasty weather conditions. At the beginning of the cruise, we expected to spend as much as a fifth of the 47-day cruise hove to and unable to work, so we cautiously estimated we could make measurements at 60 to 80 stations. In the end, despite taking on everything the Labrador Sea could throw at us, we made more than 160 stations and brought home a fine data set for the scientific party.

You had an unexpected passenger on that voyage, didn’t you?

That’s true. Off Greenland, a snowy owl came aboard and took shelter under the bulwarks on the bow. The weather was rough, but when we got a calm day, we’d go out to the bow to give water to this owl hopping around out there, but the water froze quickly. We’d try to feed it fish or chicken, but that wasn’t working. We had a Canadian oiler onboard who said, “I got some of those around the neighborhood, and we feed them bacon.” Sure enough, it did like raw bacon.

After a few days, the bird was looking tired and snow began to build up on its feathers, so a couple of us protected ourselves with grinding masks and leather arm guards, threw a blanket over it, and moved it inside a van. Everyone was so interested in the owl that we had to limit visiting hours. It came all the way across the Labrador Sea with us, and we released it as we approached the Canadian coast.

Any other Knorr stories?

In 2001, we were off Somalia, and I truly believe we saw pirates out there. The scientists needed to stop do three measurements of the flow through the choke point between the horn of Africa and Socotra Island. We sighted a slow fishing-type vessel with no active fishing gear that set a course to intercept. We actually bluffed them and came to a screeching stop. They turned and headed for the coast, and we completed our scientific mission. I think it was that the Knorr has a certain “naval” look to it.

Every transit we’ve had up and down the Bosporus has been just amazing. It’s gorgeous, exciting, and busy. The ship traffic is organized into alternating northbound and southbound convoys. There are ships all around you, a tenth of a mile away, with perhaps one overtaking on the starboard side as somebody else approaches on the port side.

On one cruise there, the scientists wanted to sample the very deepest, coldest, most dense water flowing from the Black Sea, and that meant we had to go into the center lane, so to speak. Well, they didn’t find exactly what they were looking for. The scientists wanted to move further to port, into the deepest, middle part of the channel.

By this time, the southbound convoy is en route, and the pilot wants to know “What are you doing stopped in the middle of the Bosporus?” and alerts the coast guard. We did manage to get the samples and get out.

What are some of the major challenges of the job?

Keeping to timetables. Trying to fulfill the scientific mission, while balancing weather conditions and transit times to get to your next port. Convincing the chief scientist that we can’t do just one more thing because the ship can’t do 14 knots to make its scheduled transit time through the Panama or the Suez Canal on time. Sometimes it gets right down to the last hour!

Scientists have gone to great lengths to secure their limited, precious time at sea, and sometimes they say they would like to do something. I’ve found that once you’ve demonstrated a consistent desire to do things well to the best of your ability, if you look them in the eye and say, “No, it’s unsafe or impractical,” you won’t get a contentious response.

What would you rate as your strengths as a captain?

Team building and mentoring are some of the things that I both enjoy and think I’ve had some success at doing. Fostering a positive learning atmosphere and supportive network in the small community aboard a ship.

There’s a historic perspective of seafaring in which the deck department doesn’t play nice with the engine department, and then in oceanography there’s a third player in the scientific party. Maintaining an open dialogue between the deck, the engine room, and the scientists, it’s possible to accomplish amazing things—and arrive on schedule at the next assignment. You know: “can do”— right up to the limits of safety and common sense. It allows everyone to work well together another day.

What are the biggest changes you’ve seen over your career?

Ship-to-shore communication is the major change. Going further back, my Dad would have said, “I remember leaving Woods Hole, maybe heading for Bermuda—you would be in single-side-band radio contact for a day or so and then lose it. When you got to Bermuda, you could receive telexes through the agent, and then depart once again over the horizon, with no communication.”

When I joined Knorr in the late 1970s, Capt. Hiller was a ham radio operator. He worked with Kent Swift in Falmouth, a guy named Bud Santos in Barnstable, and another contact on the West Coast to help those at sea keep in touch. People would line up outside the captain’s cabin waiting to do the occasional ham-radio patch.

Now, with e-mail, we sometimes have “virtual” chief scientists in their laboratories onshore who can be in such tight contact with the ship that they can request that we change course or to try to close up on a certain feature. Recently, when we were working about 60 miles off the California coast, many aboard the ship were in cell phone range the whole time. E-mail also allows us to keep better in touch with our families

Is the seafaring lifestyle hard on the family?

Do you mean, “What would draw somebody to choose going to sea over a desk job?” You really need to be willing to spend the time away to gain significant blocks of time ashore. You’re able to have six weeks or two months off straight, and that affords you opportunities with family and children that you can’t do easily on a 9-to-5 job.

We had busman’s holidays: We love to go boating. With my wife and two daughters, as infants in tiny lifejackets, we’d get out in Great Harbor in a skiff, or a little later in a little bigger boat go over to Tashmoo for a picnic.

My schedule may have not been optimum from many people’s viewpoint, but from my perspective, it’s worked out quite well, and from the input of my children, who are now 21 and 18. When I looked at a shore job about five years ago, they said, “What do you mean you’re going to be home nights and weekends? But then you won’t be captain.” I took that as positive reinforcement of what I had chosen.

My wife Karen has obviously been key. Without her support, strength, and understanding, this career would not have worked out.

Did you ever consider doing anything besides going to sea?

A musician. That never panned out, but I always carry my guitar when I’m shipping.

Slideshow

Slideshow

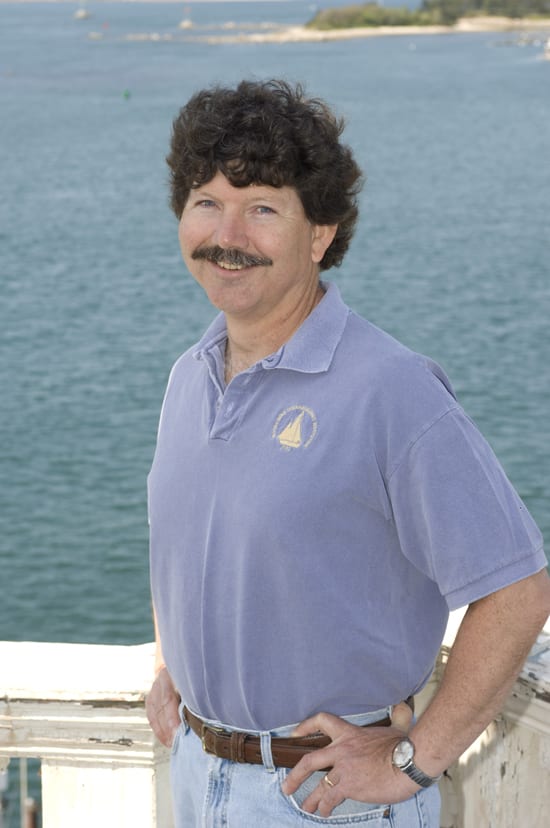

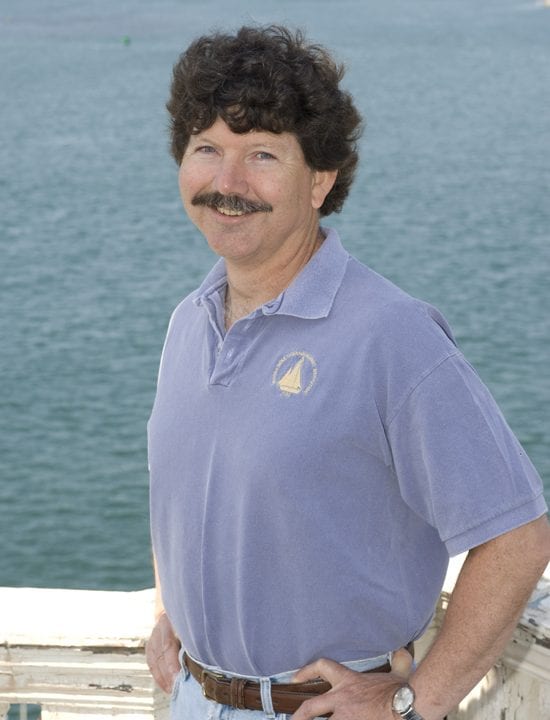

- A.D. Colburn III was named master of the WHOI-operated research vessel Atlantis in Janurary 2007. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

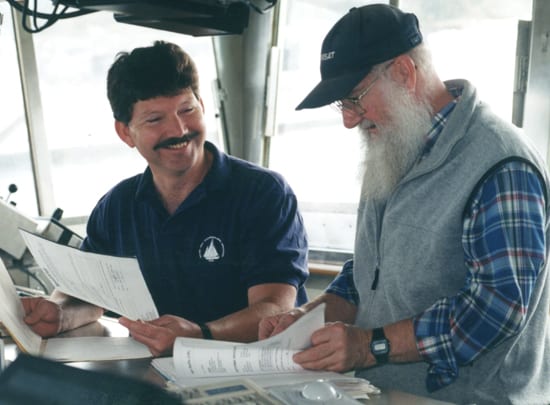

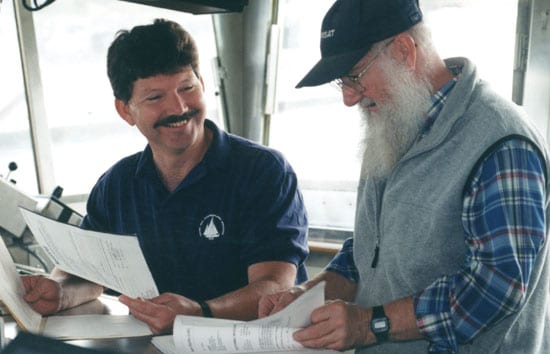

- A.D. Colburn consults with WHOI Marine Department electronics technician Steve Page on the bridge of R/V Knorr in 2001 during a call in home port. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- A.D. Colburn gets a hug from his daughter Katie after returning from a research cruise aboard Atlantis IIin 1988. (Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

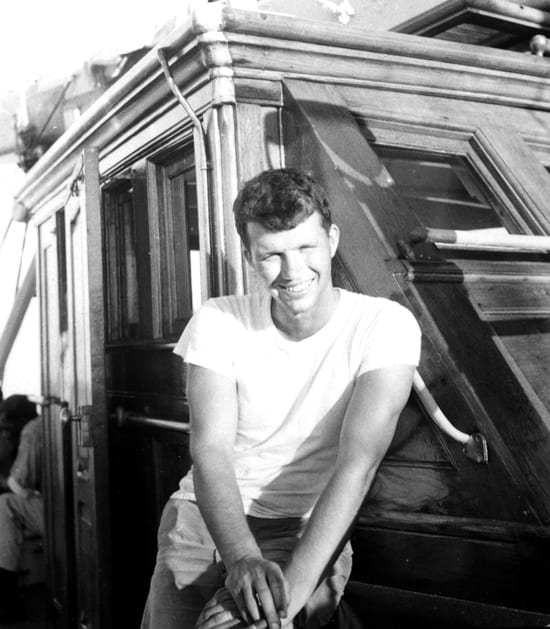

- Dick Colburn, A.D.'s father, stands outside the wheelhouse of WHOI's first oceanographic research vessel Atlantis in the late 1950s. Dick Colburn was the last master of the first Atlantis. (WHOI Archives)

- Capt. A.D. Colburn (right) took his turn, along with the rest of the crew of Knorr, chipping ice off the ship's superstructure on a cruise to the Labrador Sea in the winter of 1997. (George Tupper, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

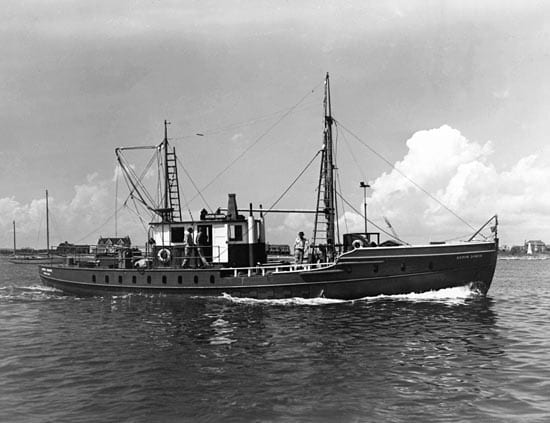

- The 143-foot ketch, Atlantis was christened in 1931, shortly after Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution was founded. (Courtesy of WHOI Archives)

- Atlantis II, shown here on a cruise to the Black Sea, served the oceanographic community from 1963 to 1996.

- WHOI's third Atlantis was christened in 1997. (Jayne Doucette, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Atlantis, 1931-1964

Atlantis was the first Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution research vessel and the first ship built specifically for interdisciplinary research in marine biology, marine geology and physical oceanography. Columbus Iselin, her first master and a major influence in her design, felt that speed was not essential; steadiness, silence and cruising range were of primary importance.

Once built WHOI searched for an appropriate name for the research vessel. A trustee of the Institution, Alexander Forbes, had recently bought a schooner named Atlantis from Iselin. Mr. Forbes rechristened his schooner so the new research vessel could be named Atlantis.

The "A- boat" made 299 cruises and covered 700,000 miles, doing all types of ocean science. In 1966, Atlantis was sold to Argentina, refurbished, and renamed El Austral. It is used as a research vessel and is crewed by Argentine naval personnel.

Specifications

Built: 1931 in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Designed by Owen and Minot specifically for WHOI

Length: 143' 6"

Rig: Marconi Ketch

Sail Area: 7,200 sq. ft.

Beam: 29'

Main: 144' from water line

Draft: 18'

Mizzen: 100' from water line

Capacity: crew- 19, science- 9

(Photo courtesy of WHOI Archives) - Asterias, 1931-1980

Named for the local starfish, Asterias was built of white and southern hard pine and was similar in design to commercial fishing boats of the era. The Asterias and the Atlantis were built as the Institution's first vessels.

The first Asterias made at least 10,000 short trips, from Maine to New York, primarily for the testing of scientific gear. Nearly every member of the scientific and technical staff had a need for Asterias at some time. Her excellent design and construction made her a natural seaboat.

Asterias was sold to Ocean Research Engineering in 1980. In 1985 Edwin Athearn, her former captain saved her from destruction and together with Dave Lewis restored the ship's name and condition.

Specifications

Built: 1931 by the Casey Boat Building Co., Fairhaven, MA, for WHOI

Length: 40.5'

Beam: 13.6'

Draft: 5'3"

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Anton Dohrn, 1940-1947

Anton Dohrn was given to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in June 1940 for local-area scientific work. The vessel made at least 40 cruises from the Gulf of Maine to the coast of New Jersey, testing bathythermographs, underwater cameras, and other newly designed instruments, and conducting underwater sound transmission experiments and harbor studies. According to Dick Edwards, WHOI Marine Superintendent for many years, it took eight bilge pumps to keep Anton Dohrn afloat.

The vessel was sold in April 1947 and was to be used as a mail boat between New Bedford and Cuttyhunk Island.

Specifications

Built: 1911 in Miami, Florida, for the Carnegie Institution

Length: 70'

Beam: 16'9"

Draft: 6'

Capacity: crew- 29, science - 17

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Balanus, 1946-1950

Balanus was used during the war years as a harbor transport. WHOI purchased the vessel in 1946 from Vita Lo Piccola of Boston for use primarily in coastal waters. Balanus made 26 cruises. Her work was mainly for physical oceanography, but also included plankton tows, camera work, instrumentation tests and current measurements. Balanus was sold in 1950 to D.L. Edgerton, a MD fisherman.

Specifications

Built: 1940-41 by Reid, Winthrop, MA.

Designed: Eldredge-McGinnis Co., Boston, MA, as a dragger

Length: 75'

Beam: 18'

Draft: 8'

Capacity: crew - 8, science - 5

Names: Little Sam (Q-68) 1941-1946

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Caryn, 1948-1958

Rumor has it that Caryn was originally built specifically for smuggling. When the vessel was first launched, she carried 4,000 square feet of canvas. WHOI purchased Caryn in 1947 from her third owner, C.R. Hotchkiss of New York.

At WHOI, Caryn made 110 cruises, mostly along the East Coast through the Caribbean and around Bermuda. All types of oceanography were undertaken. The vessel was sold in 1958 to S.H. Swift, was renamed Black Swan, and engaged in charter trade. On New Year's Eve, 1974, at St. Maarten?s Island, West Indies, the vessel burned.

Specifications

Built: 1927 in Singapore by C.E. Nicholson

Length: 97.9'

Beam: 21'"

Draft: 11'3"

Names: Black Swan 1927-1930,

Santa 1930-1935,

Marie 1947-1948,

Caryn 1948-1958

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Albatross III, 1948-1958

The vessel first sailed under the name Harvard for the North Atlantic Fishery Investigations. In 1941 she was rebuilt, renamed Bellefonte and used by the US Navy for war patrol. Upon her return to Woods Hole in 1944, under the name Albatross III, the vessel was used intermittently until 1955, when funding became available. Albatross III was under full operation until 1959, when decommissioned and sold to a Hyannis, MA, fisherman.

Albatross III was loaned to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution from 1951-1952, and was also used jointly on other cruises from 1948-1959. Albatross III made a total of 128 cruises, all in the North Atlantic. Most of these were part of fisheries investigations, but many cruises included hydro stations, bottom photographs, drift bottle exercises, and current measurements.

Specifications

Built: 1926 as a steam trawler

Length: 179'

Beam: 24'

Draft: 12'

Capacity: crew - 21, science - 6

Names: 1926 as a steam trawler Harvard 1926-1941, Bellefonte, 1941-1948, Albatross III 1948-1959

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Bear, 1951-1963

Built during WWII as a troop carrier in the South Pacific, Bear was chartered by WHOI in 1951 and purchased in 1952. The vessel made 192 cruises in the western North Atlantic, venturing as far east as Bermuda. Bear made acoustic, bathymetric and seismic measurements, and participated in fish observations.

The vessel was sold in 1963 to a New Bedford fisherman and refitted as a scalloper.

Specifications

Built: 1941-1942 by Herreshoff, Bristol, RI, as a coastal transport

Length: 103'

Beam: 21'

Draft: 10'

Capacity: crew-23, science-36

(Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Crawford, 1956-1969

Crawford, a former US Coast Guard cutter, was transferred to WHOI in 1956. The ship underwent considerable renovation at Munro Shipyard in Boston, including an increase in her fuel capacity giving her a range of 30 days and 6,000 miles. She worked in the North and South Atlantic, including the Caribbean Sea amd carried specialized gear for studying hurricanes. The vessel was mainly used for working on hydrographic stations, in long line fishing studies, and in surveying for Texas Towers.

In a novel attempt to increase working space on the vessel, an aircraft wing was attached to her port side in 1980, though it was later dismantled and the experiment was never repeated.

Crawford made 175 cruises for WHOI until 1968. In 1970 the vessel was sold to the University of Puerto Rico.

Specifications

Built: 1927, Great Lakes

Length: 125'

Beam: 23'

Draft: 12'3"

Capacity: crew-17, science-9

(Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Aries, 1959-1960

The Aries, a 93 foot ketch, arrived in Woods Hole in March 1959 as a gift from R.J. Reynolds. She was refitted as a research vessel by June 1959 and was then used continuously on current measuring cruises off Bermuda as part of a joint project shared by WHOI and the British National Institute of Oceanography until August 1960. Her longest stay ashore was from December 14th, 1959, until February 2nd, 1960, when her engine was replaced by the a spare reconditioned and brought from England. Bermuda proved to be a particularly good base for the Aries since her fresh water storage limited her time at sea to about two weeks. Aries spent a total of 206 days at sea, 186 days of which were on cruises to deep-water, and of this deep-water time 129 days were spent in the selected working area. Captain J. W. Gates was in charge until after the refit when Captain H. H. Seibert took over until the end of the project. Mr. C. L. McCann was mate for the entire period.

Specifications

Built: 1953

Length: 93'

Beam: 19'6"

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Chain, 1958-1979

In 1958, the Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS), took over the operation of Chain, a Navy salvage vessel, and under an agreement with the Navy, the ship came to Woods Hole. Chain's first nine cruises at WHOI were made with an MSTS crew. In 1959, WHOI assumed operation of the vessel.

Chain made a total of 129 scientific cruises, including a cruise that took her around the world in 1970-1971. She traveled some 600,000 miles and was used in every type of ocean science. Long a favorite for her seaworthiness, Chain's last cruise ended in December 1975. In June 1979 the vessel was towed away for scrap.

Specifications

Built: 1944 by the Basalt Rock Co., Napa, CA

Length: 213'

Beam: 41'

Draft: 16'16"

Capacity: crew-29, science-26

(Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Anton Bruun, 1962-1964

Aras, a long graceful steel ship, was originally built for Hugh J. Chisholm of the Oxford Paper Co. as a private yacht. The US Navy purchased the vessel in April 1941, for $250,000, for use as a patrol gunboat and re-christened it USS Williamsburg.

In 1945, after a successful tour of duty in the North Atlantic, Williamsburg was to be converted to an amphibious-force flagship. Instead, she was refitted at the Naval Gun Factory, Washington, DC, as President Truman's yacht. President Eisenhower decommissioned the yacht in 1953 due to her high operating costs. The National Science Foundation acquired the vessel on 8/9/1962, refitted it for science, and christened it Anton Bruun in memory of the noted Danish marine biologist who chaired the first International Oceanographic Commission.

The vessel was chartered to WHOI for the International Indian Ocean Expedition, originally for a 4 year period. Anton Bruun made 9 legs of a cruise for this project, from March 1963 to December 1964, and then returned to the Navy in late December 1964. In 1980 the Endangered Properties Program planned to restore the vessel, but as late as 1984 nothing had been done.

Specifications

Built: 1931 by Bath Iron Works, Maine

Length: 244'

Beam: 36'

Braft: 16'

Names: Aras 1931-1941,

USS Williamsburg (PG-56) 1941-1962,

Anton Bruun 1962-1964

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Atlantis II, 1963-1996

Atlantis II was named for the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution's first research vessel. Long considered the flagship of the Institution's fleet, the ship traveled around the world and was involved with every type of ocean science investigation.

In 1979 Atlantis II underwent a major mid-life refit. The conversion of the vessels power source from steam to diesel reduced the vessel's operating cost, increased its range of travel, and increased its selection of ports.

In 1983 a deck hanger and A-frame were installed enabling her to handle the launch and recovery of the submersible Alvin. Atlantis II served as Alvin's tender from 1984 to 1996.

Atlantis II concluded 34 years of service, over one million miles sailed for science, and more than 8,000 days at sea, a record unequaled by any research vessel. In 1996 she was delivered to Shaula Navigation, based in Boulder CO for rechristening as Antares and a planned new career as a fisheries research vessel in the North Pacific and Gulf of Alaska.

Specifications

Built: 1963 Maryland Shipbuilding and Drydock Co., Baltimore, MD.

Designed: Bethlehem Steel Central Technical Dept., Quincy, MA, and M. Rosenblatt and Son, NY

Length: 210'

Beam: 44'

Draft: 17'

Speed, full: 13.5 knots

cruising: 12 knots

Endurance: 45 days

Capacity: crew-31, science 25

(Photo courtesy of WHOI Archives) - Gosnold, 1962-1973

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution purchased Explorer, a coastal cargo ship, in March 1962 from a marine salvage yard. As a way of distinguishing this ship from the many other "Explorers in existence, it was named Gosnold by its master Harry Seibert, naval architect John Leiby, and Port Captain John Pike in honor of the captain Bartholomew Gosnold, the first European to land and settle in Woods Hole (1602). The vessel made 206 cruises from Maine to South America and out to Bermuda, covering all types of ocean sciences. Gosnold was transferred to the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, Florida, in October 1973, where it continued to work.

Specifications

Built: 1943 for the US Army at Kewanuee Shipbuilding Co.

Length: 99'

Beam: 21'6"

Draft: 11'

Capacity: crew -6, science - 7

Names: Explorer (F-76) 1943-1962, Gosnold

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Lulu, 1965-1984

In March of 1965, Lulu headed to Florida, under tow, for the first test as the submersible Alvin's tender. The vessel began making regular trips with Alvin aboard in May 1965. Lulu made 119 cruises in the North Atlantic Ocean, including the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Azores area, the Caribbean Sea, and in the eastern Pacific.

Lulu's last trip was in August of 1983. In September 1984, Lulu was transferred to San Diego for Navy use as tender to the submersibles Sea Cliff and Turtle, but was instead sold to private owners.

Specifications

Built: 1963-1964 in Woods Hole from two 96' Navy surplus mine sweeping pontoons by Dan Clark, Inc.

Length: 105'

Beam: 48'

Draft: 11'

(Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Knorr, 1970-present

Knorr was delivered to WHOI in April 1970. R/V Knorr (AGOR-15) was named in honor of Ernest R. Knorr, a distinguished early hydographic engineer and cartographer who was appointed senior civilian and Chief Engineer Cartographer of the US Navy Hydographic office in 1860.

Knorr is an all purpose scientific vessel designed to accommodate a wide range of oceanographic tasks. Its forward and aft azimuthing propellers allow the ship to move in any direction or to maintain a fixed position in high winds and rough seas. The vessel's other unique features, like anti-roll tanks and ice strengthened bow, enable Knorr to travel the world's oceans.

In 1991 Knorr returned to WHOI after undergoing a 32 month major mid-life refit. The vessel was upgraded and refitted at the McDermott Shipyard in Amelia, Louisiana. An additional 34' was added to Knorr's length at the middle providing room for a new laboratory and machinery space. In addition, Knorr's twin azimuthing propulsion system was installed.

Sister ship: Melville, operated by Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego.

Specifications

Built: 1968 by Defoe Shipbuilding Co., Bay City, Michigan. Designed and built under the direction of the Naval Systems Command, Supervisor of Shipbuilding, 9th Naval District

Length: 245' originally, 279' after refit

Beam: 46'

Draft: 16'

(Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Alcoa Seaprobe, 1977

Alcoa Seaprobe, an all-aluminum vessel built specifically for deep ocean research and recovery, had a unique search pod enabling it to sweep the ocean floor and transmit data to the ship. The vessel could also core, drill, and sample mineral deposits down to 18,000 feet. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution used Alcoa in the 1970s to conduct tests of the ANGUS camera sled, and the Westinghouse side-scan sonar for pressure tests, and for underwater filming and photography.

Specifications

Built: 1970 by ALCOA (Aluminum Co. of America)

Length: 243'

Capacity: Crew-33, science-19

(Photo courtesty of WHOI Archives) - Oceanus, 1977 to present

Oceanus arrived in Woods Hole in November of 1975. The vessel is owned by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and operated by WHOI. She has worked extensively in the Atlantic on a variety of biological, chemical, geological, physical, and engineering cruises.

In 1994 Oceanus underwent an extensive 8 month mid-life refit at Atlantic Drydock in Jacksonville, Florida. The NSF provided a grant for the $3.5 million project to refit and upgrade the vessel's technology, equipment, and laboratories.>

Sister ships: Wecoma, operated by Oregon State University, and Endeavor, operated by the University of Rhode Island.

Specifications

Built: 1975 by Peterson Builders Inc., Sturgeon Bay, WI. Designed by John W. Gilbert Assoc., Inc., Boston for University-National Oceanographic Laboratories System (UNOLS).

Length: 177'

Beam: 33'

Draft: 17'6"

Full Speed: 14.5

Cruising Speed: 11.5

Endurance: 30 days

Capacity: crew-12, science-12

Capacity: Crew-33, science-19

(Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - Atlantis, 1997-present

Atlantis replaced the Atlantis II and was named for WHOI's original research vessel. She made her first call in home port on April 1997. The new Atlantis has advanced support facilities to service and launch submersibles, such as Alvin, and a wide variety of ROVs at locations throughout the global oceans. She is one of the most sophisticated research vessels afloat, equipped with precision navigation, bottom mapping, and satellite communications systems.

Atlantis is owned by the US Navy and operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in support of the US academic ocean research community.

Specifications

Built: 1997 by Halter Marine Inc., of Moss Point, Mississippi

Length: 274'

Beam: 52.5'

Draft: 17'

Capacity: crew-23, science-36

(Photo by Tom Kleindinst, WHOI) - Tioga, 2004-present

R/V Tioga is an aluminum hulled coastal research vessel that serves ocean scientists and engineers working in the waters off the Northeastern United States and is solely owned by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. This small, fast research boat was designed and outfitted for oceanographic work close to shore. Speed allows Tioga to operate in narrow weather windows, meaning researchers can get out to sea, complete their work, and make it back before approaching foul weather systems arrive. Tioga can accommodate six people for overnight trips—including the captain and first mate—and up to 10 people for day trips. The boat is equipped with water samplers, a current profiler, and an echo-sounder, used by scientists to conduct seafloor surveys. Tioga has two winches, including one with electrical wires to collect real-time data from towed underwater instruments. Buoys can be deployed using the A-frame on the stern, which is similar in size to those on WHOI’s large ships.

Specifications

Built: 2004

Length: 60 feet

Beam: 17 feet

Draft: 5 feet

Capacity: crew-2 (additional required for extended trips), science-6 bunks (10 people on day trips)

(Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Related Articles

Topics

See Also

- WHOI Ships and Technology

- A Portrait of Capt. Emerson Hiller from the WHOI 75th anniversary archive