The Harshest Habitats on Earth

Life blooms in Deep Hypersaline Anoxic Basins

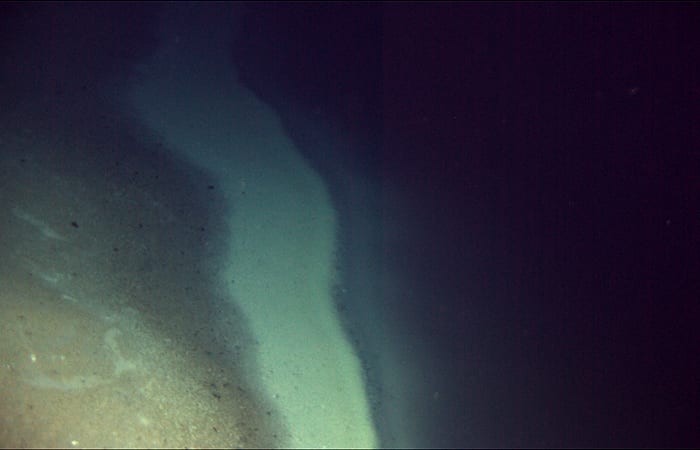

As the remotely operated vehicle Jason approached the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea, its cameras relayed an eerie scene back to the research vessel Atlantis. It looked like a dark lake on the seafloor.

A narrow white stripe meandered across the brown seafloor like a beachfront; beyond it lay an impenetrable blackness. When the vehicle nosed closer, the water around it shimmered like waves of heat above a summer road, and cloudy wisps streaked the view ahead.

Jason was giving scientists their first clear look at a Deep Hypersaline Anoxic Basin, or DHAB (dee-hab). These depressions on the seafloor—utterly dark and under pressure up to 350 times higher than on land—are filled with water that is totally lacking oxygen and up to ten times saltier than normal seawater. They would seem to be more hostile to life than anywhere else on Earth.

Yet they are home to thriving communities of microbes, and what Virginia Edgcomb and her colleagues are finding in them is challenging our ideas about the very conditions necessary for life.

Hints of life

“Often, microbes only have to adapt to one ‘extreme’ factor, such as a lack of oxygen or very high pressure,” said Edgcomb, a microbial ecologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI). “What’s interesting about the DHABs is that there are multiple stress factors involved.”

When bacteria and archaea, another domain of single-celled life forms, were discovered living in Mediterranean DHABs about ten years ago, it wasn’t a huge surprise. Those forms of life have been found in a variety of incredibly harsh environments. But most biologists thought that higher forms of life—eukaryotes, whose cells contain a nucleus and other organelles—probably couldn’t survive there.

Then in 2009, scientists examining DHAB water samples found DNA and ribosomal RNA from protists—single-celled eukaryotes similar to Amoeba and Paramecium. That didn’t necessarily mean the protists were living in the DHABs. DNA can persist in some environments for thousands or even millions of years, and DHAB brine is salty enough to preserve just about anything. Maybe the DNA and the ribosomal RNA had come from protists that had drifted into the DHABs and, in effect, been pickled.

But the finding raised a tantalizing possibility. For Edgcomb and WHOI geobiologist Joan Bernhard, who have studied protists from hostile habitats around the planet, figuring out what was really going on in DHABs was an irresistible challenge.

Tiny targets

DHABs were discovered in the eastern Mediterranean in the 1980s and have also been found in the Red Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and a few other locations. Those in the Mediterranean range from a few hundred yards to a few miles across, and from ten yards to 500 yards deeper than the surrounding seafloor. They formed between 2,000 and 35,000 years ago, when movements of Earth’s crust exposed long-buried salt deposits to seawater. The salt and other minerals began to dissolve, and the resulting extra-salty, ultra-dense water got trapped in valleys on the seafloor.

The brine has stayed in the basins ever since, isolated from the less dense water above it and from other DHABs nearby. Today the basins all have different concentrations of sodium and magnesium salts. Some contain toxic sulfides or methane, and many have other unique chemical signatures.

Edgcomb, Bernhard, and collaborators from Greece, Germany, and Italy were especially interested in exploring the interface zone between normal seawater and DHAB brine below. Conditions are close to normal near the top of the interface and get progressively harsher nearer the DHAB. The differences in density along that gradient created the shimmery effect caught by Jason’s cameras.

Most DHAB interfaces are just one to three yards thick, and within that short space each vertical millimeter presents a different menu of challenges and opportunities to potential residents. The sloping area where the interface meets the seafloor—the white stripe researchers later dubbed “the beach”—likewise offers a range of conditions that might support a diverse fauna.

“It’s thought that the interfaces represent a sort of smorgasbord,” said Edgcomb. “There are so many different types of conditions along that gradient that it could allow a very diverse community of microorganisms to co-exist in close proximity to one another.”

The right tools

To see that diversity, though, would require sampling from different levels less than a yard or two apart, more than two miles down. Until recently, that level of accuracy was not possible. Over the past few years, Edgcomb and her colleagues have made several trips to Mediterranean DHABs, most recently with equipment that let them precisely identify their sampling areas in DHABs and preserve the collected cells in situ—at the site of collection. That way the cells do not degrade during the several-hour trip back to the surface, a problem that had plagued previous attempts to collect living deep-sea protists.

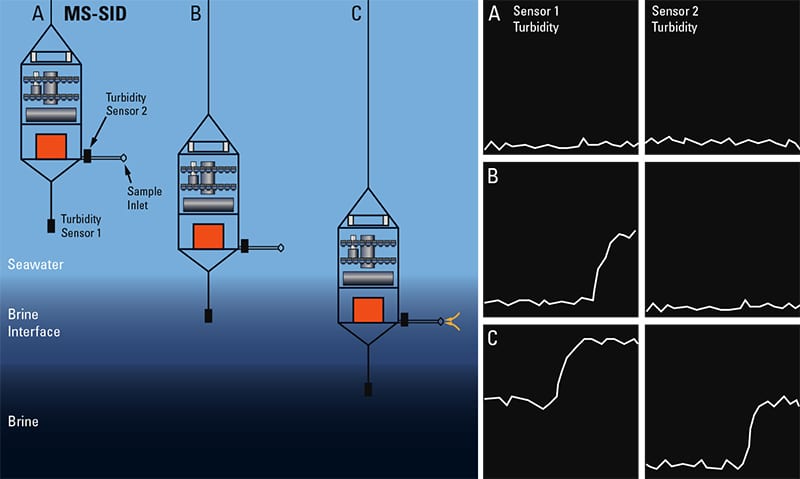

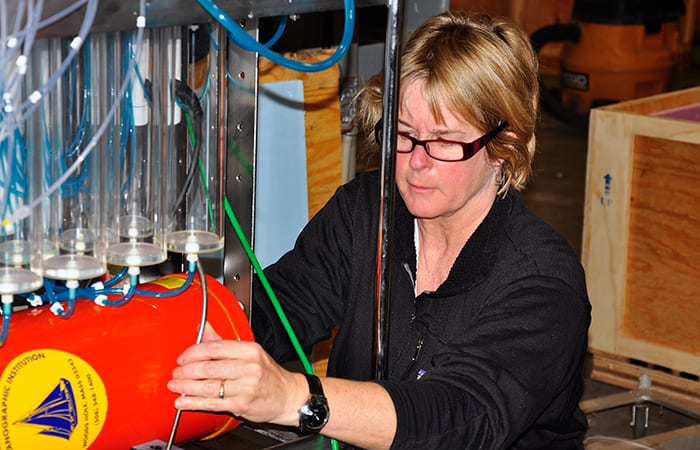

To collect organisms living in the water, they used two versions of the Submersible Incubation Device (SID) developed at WHOI by microbiologist Craig Taylor, Edgcomb, engineer Ken Doherty, and McLane Research Laboratories. To collect organisms living in the sediment, they called on Jason’s skilled pilots to use the vehicle’s video cameras and manipulator arms to gather and preserve material from specific locations.

Bernhard, who spearheaded the sediment work, said Jason did a beautiful job collecting material from the beach and the normal seafloor, but had trouble penetrating into a DHAB even with its downward thrusters revved up all the way. The brine was so dense that the vehicle’s sensors thought the top of the DHAB was actually solid seafloor. After several tries, the pilots were able to “park” Jason in the interface zone and reach a manipulator arm down into the murk to collect DHAB sediment.

A lively realm

When the samples reached the ship, some of the collected cells were prepared for microscopic examination. Most were processed to extract two kinds of RNA (ribonucleic acid) that would reveal what kinds of organisms were present and what metabolic activities they were carrying out. RNA, particularly messenger RNA (mRNA), is a better molecule for this study because, unlike DNA, it normally degrades soon after the cell that made it dies. If you find mRNA from a particular kind of cell, that cell probably hadn’t been pickled; it was alive at the site when you collected it.

The samples yielded thousands of RNA sequences, which the researchers are analyzing with bioinformatics techniques. The results so far are striking. Both DHABs and interface zones are home to many kinds of bacteria but few archaea. Both also have diverse populations of eukaryotes, especially fungi and ciliates, protists with hair-like structures. Most of those are probably previously unknown species.

Recipe for life

The precise sampling made possible by the SID instruments revealed that the microbes living at different levels of the interface perform different functions, presumably due to the different conditions they live in.

“The eukaryotes are not doing the same things and living in exactly the same way only a couple of yards apart,” said Edgcomb. “It’s very cool.”

Konstantinos Kormas, a microbiologist from the University of Thessaly in Greece who recently finished a sabbatical at WHOI, said the interface appears to be especially active.

“The overlying water column is very poor in terms of protists eating bacteria,” said Kormas. “But in the interface, suddenly it’s like hitting an oasis. Suddenly everybody is eating everybody.”

“It is a hotspot,” agreed Maria Pachiadaki, a postdoctoral investigator in Edgcomb’s lab. “There is a lot of recycling of carbon happening in the interface.” She said it’s likely that some of the protists are predators, hunting and eating bacteria, and some are scavengers, dining on the remains of their neighbors or on organic detritus that drifts down from the waters above.

Noted scientist Ed Leadbetter, who investigated microbial metabolism during a 46-year career at Amherst and the University of Connecticut, is helping to piece together an overall picture of how organisms with different metabolic capabilities interact in the DHAB ecosystem.

The researchers will be on the lookout for partnerships between protists and bacteria. For several years, Bernhard has been working with protists that survive anoxic or sulfidic conditions by hosting symbiotic bacteria. She and Edgcomb have shown that the bacteria perform such duties as detoxifying chemicals that would otherwise kill the protists. In return, said Bernhard, “The bacterial symbiont benefits because the protist can migrate to wherever the right geochemical conditions are, and that’s keeping the bacteria in a ‘happy place.’”

Islands in the sea

Another intriguing result is that there’s very little overlap of species among the various habitats the team sampled. A few types of protists that live in normal seawater are found in the upper interface zone, but as a whole, the communities in normal seawater, the DHABs, and the interfaces between them are different.

Not only that, but different DHABs that the scientists have sampled all have completely different residents.

In effect, said Edgcomb, each basin is like an island. With its residents unable to travel through normal seawater to other basins, each DHAB has evolved its own unique fauna. She said that makes sense when you remember that each DHAB has a distinctive chemistry derived from the distinctive salt deposits that formed it. Each set of chemical conditions would exert different kinds of pressure on the organisms living there, selecting for ability to endure high sulfide or methane, for instance.

“Chemistry appears to be driving the differences in the communities,” she said.

She suggested that when the DHABs first began to develop, some microbes from normal seawater were able to survive in the slightly saltier water of the basins. Over time, as the basins became saltier and lost oxygen, only individuals that could adapt to the increasingly harsh conditions persisted and reproduced. Now, after thousands of years of evolution in a unique chemical environment, each basin is home to a unique set of species.

Edgcomb, Bernhard, and their colleagues are now taking a close look at how these organisms are able to thrive in conditions where mere survival was thought to be impossible. Wherever they came from, whatever their survival strategies, the DHAB eukaryotes have already redefined the limits of life.

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft of Germany, and National Research Council of Italy.

Slideshow

Slideshow

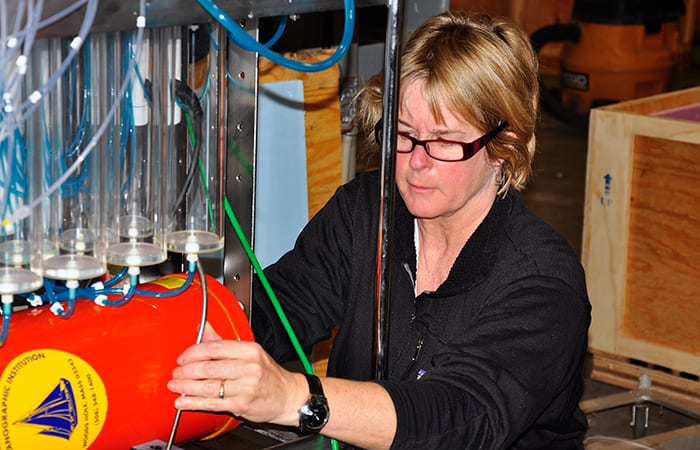

WHOI microbial ecologist Virginia Edgcomb assembles part of MS-SID, a robotic underwater laboratory and sampling instrument that enabled her to collect and preserve microbes from specific areas more than two miles deep in the Mediterranean. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

WHOI microbial ecologist Virginia Edgcomb assembles part of MS-SID, a robotic underwater laboratory and sampling instrument that enabled her to collect and preserve microbes from specific areas more than two miles deep in the Mediterranean. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)- The day before embarking for the Mediterranean DHABs, geobiologist Joan Bernhard and Jason expedition leader Tito Collasius reviewed the pushcores and other equipment they would use to collect sediment samples during the cruise. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Remotely operated vehicle Jason being launched into the Mediterranean Sea from the research vessel Atlantis in December, 2011. Jason carried powerful lights, high-definition still and video cameras, two manipulator arms, sampling equipment, and sensors that recorded salinity, density, and depth. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- ROV Jason sent back images of normal Mediterranean seafloor (left), the murky water of a DHAB (right), and the white "beach" between them. Researchers from WHOI and other institutions were able to sample water and sediments from all three zones, thanks to Jason and the new sampling robot MS-SID. (Virginia Edgcomb, WHOI/NSF/ROV Jason/©WHOI)

- Visible ripples appeared when Jason moved into the interface zone, indicating that layers of water of different densities were mixing. At upper right, one of Jason's manipulator arms retrieves a pushcore tube containing sediment from the interface. (Virginia Edgcomb, WHOI/NSF/ROV Jason/©WHOI)

- A pushcore retrieved by ROV Jason from the interface zone of a Deep Hypersaline Anoxic Basin (DHAB). Geobiologist Joan Bernhard, who led the sediment work on the cruise, said pushcores are of great value because they keep intact the vertical layering of the sediments. In this sample, the top inch or so is rich in bacteria and protists. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Microbial ecologist Konstantinos Kormas of the University of Thessaly and undergraduate Colin Morrison of the University of Nevada-Reno scoop sediment from a DHAB out of a collection chamber. This kind of chamber allows researchers to collect a lot of material, but does not preserve the layered structure of the sediments. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI microbiologist Craig Taylor and postdoctoral investigator Maria Pachiadaki attach a turbidity sensor to a chain hanging from the MS-SID. They used data from this sensor and another one attached directly to the instrument to determine when MS-SID was in a DHAB or its interface zone, which allowed them to take samples from very specific areas. (Photo by Cherie Winner, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Turbidity sensors on the MS-SID enabled scientists to sample within the thin interface between a DHAB and the overlying seawater. Turbidity was high in the interface and even higher in the DHAB, due to particles trapped in the high-density water. (Illustration by Craig Taylor, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Video

Related Articles

Topics

Featured Researchers

See Also

- What are DHABs? A Dive & Discover infomod on Deep Hypersaline Anoxic Basins.

- Dive & Discover mission to the Mediterranean Daily updates from a cruise to Mediterranean DHABs.

- An Ocean Instrument is Born Oceanus magazine story about the development of SID, the Submersible Incubation Device.

- ROV Jason Learn more about this deep-sea exploration vehicle.