To Track a Sea Turtle

Underwater vehicles follow tagged turtles in the wild

Kara Dwyer Dodge grew up hearing stories of the sea monster her father pulled from the ocean.

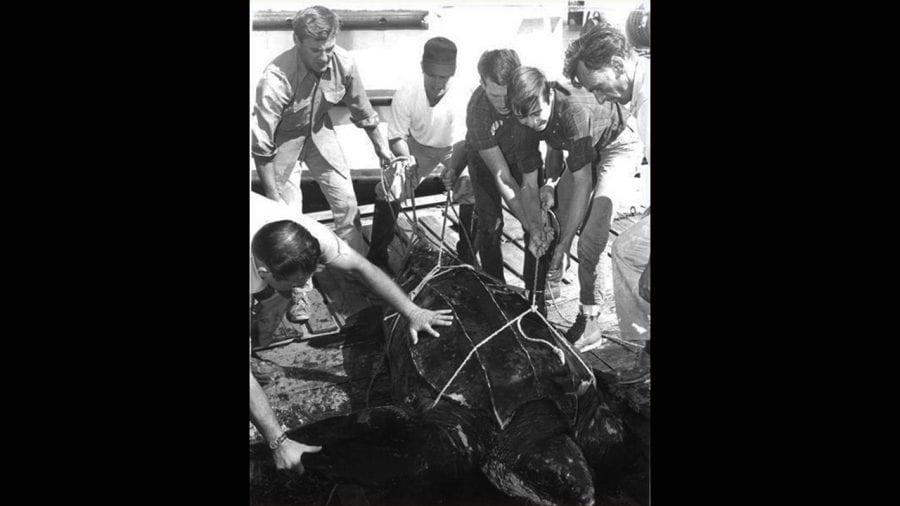

In 1966, Richard Dwyer, a third-generation fisherman in Scituate, Mass., found a sea turtle entangled in the lines of one of his lobster pots. He freed it and brought it back to shore, where the turtle became a minor sensation because no one could remember ever seeing one so large so close to shore. After a couple of days, Dwyer took the turtle far offshore and released it in the Gulf Stream, where he thought it should be, rather than the waters near Cape Cod.

“No one knew then that this is part of their natural range,” said Dodge.

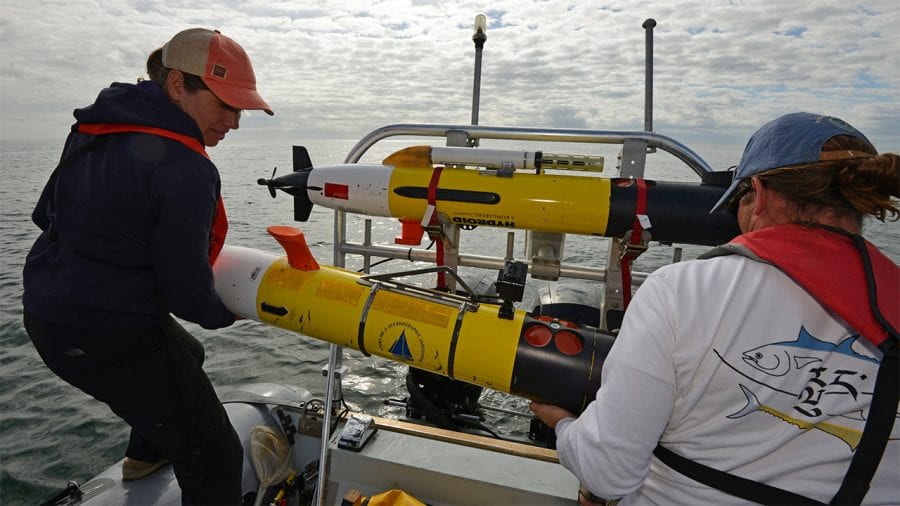

Today, the daughter of a fisherman is a marine biologist and guest investigator at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), studying the behavior of sea turtles as a way to help prevent things such as entanglement in fishing gear. In 2013, she teamed up with WHOI engineer Amy Kukulya, who with colleagues at WHOI’s Oceanographic Systems Lab (OSL) had built SharkCam, a system using an autonomous underwater REMUS vehicle to track sharks in the wild. Kukulya joined with biologists Greg Skomal from the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and Mauricio Hoyos Padilla at the Mexican marine conservation organization Pelagios Kakunjá to tag and follow nearly a dozen sharks in the waters around Cape Cod and Guadalupe Island, Mexico, and reveal previously unknown shark behaviors.

But tracking turtles turned out to be a much more challenging proposition. “We’d never put a suction-cup tag on an air-breather and followed it,” said Kukulya. “They tend to yo-yo rather than follow a straight trajectory. We had to develop entirely new algorithms to follow a turtle.”

To find funding for the research, they tried WHOI’s new crowd-funding platform, ProjectWHOI, plunging into the fast-growing world of social media fundraising. The pair exceeded their $10,000 goal, raising $37,000 in two months from a combination of friends, family members, strangers, corporate donors, and a Falmouth High School art class, as well as WHOI Trustee Jean Tempel, who, among her many other interests, advocates on behalf of women in science and engineering. That nest egg allowed Kukulya and Dodge to collaborate with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries to win a $270,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Atmospheric Administration, which required matching funds.

“This happened because people believed in our approach to get out on the water locally and aid conservation,” Kukulya said. “It warmed my heart to see how dedicated people were to our plight.”

With the funds, they were able to complete development of TurtleCam, including a redesigned tag with a custom-built release mechanism that Kukulya devised. In September 2016, they succeeded in tagging their first leatherback sea turtle and following it for more than six hours. That trip and three that followed resulted in a trove of video that Dodge is still combing through for insights that will help her help turtles navigate the many hazards that turtles encounter when they are near Cape Cod feeding on jellyfish.

She also has information from a second vehicle that Kukulya simultaneously deployed to gather data on temperature, salinity, biological productivity, and water depth in the water near the tagged animals. “[TurtleCam] is great to collect fine-scale behavior, but we need habitat data to make sense of what we’re seeing,” said Dodge.

Kukulya is now refining the algorithm that controls TurtleCam to keep a turtle in the field of view longer and to better adapt the vehicle to a turtle’s behavior. Next summer the two will conduct five more trips in and around Vineyard Sound. Although many North Atlantic populations of sea turtles are stable, their primary threats—entanglement, boat strikes, plastics, coastal development, and climate change—are human-caused and not likely to diminish any time soon. Dodge only has to look to areas in the Pacific, where almost all sea turtle species are in trouble, to see how dire things could become.

“I’ve dissected a lot of dead leatherbacks,” said Dodge. “I don’t want to keep doing that.”

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Marine biologist and WHOI guest investigator Kara Dodge (left) and WHOI engineer Amy Kukulya have been teaming up since 2013 to adapt Kukulya’s SharkCam autonomous tracking and imaging system to the challenge of following and filming leatherback sea turtles in their natural environment. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Dodge grew up hearing about the time in 1966 when her father, Richard Dwyer (center, in hat) accidentally caught a leatherback sea turtle in his fishing gear off the coast of Scituate, Mass. Dwyer later released the turtle further off shore in what he thought was the animal’s natural, deep-water habitat. (Photo courtesy of Kara Dodge)

- Dodge keeps watch for a sea turtle while Kukulya and Dodge’s husband Mike prepare the suction-cup tag. In previous attempts to tag a turtle, simply finding their quarry proved difficult because they present such a low profile on the water and spend a short time at the surface. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Mike Dodge prepares to tag a leatherback sea turtle. The tag stays on the turtle’s shell until Kukulya sends a coded acoustic signal that triggers a suction cup release mechanism that she designed. Cameras on the tag allow Kara Dodge to record how much a turtle eats and how often it breathes, which allows her to calculate the animal’s metabolic rate and energy consumption. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Kukulya and Dodge prepare a REMUS autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) that Kukulya and her colleagues at WHOI’s Oceanographic Systems Lab specially adapted to track and film great white sharks (bite marks are visible in the vehicle’s yellow paint). The vehicle is fitted with six GoPro cameras in special housings, enabling it to film a shark’s or a turtle’s behavior from a variety of angles. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Kukulya releases a second REMUS vehicle that she configured to gather physical, chemical, and biological data from the water near the tagged turtle. During a mission, she constantly monitors the vehicle’s position to keep it about 350 meters (1,150 feet) away. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Once tagged, a leatherback typically dives for the bottom before resuming its normal behaviors. The tag emits a coded acoustic signal that the REMUS TurtleCam vehicle can home in on. The vehicle is programmed to follow the signal and also anticipate the animal’s movements in order to maximize the time that the turtle is in the field of view of one of its six cameras. (Photo courtesy of Amy Kukulya and Kara Dodge, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, under NMFS Permit No. 15672-02)

- A tagged turtle surfaces briefly to breathe and finish swallowing a jellyfish. Sea turtles in Vineyard Sound between Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard typically spend most of their time eating—and since jellyfish are mostly water, a sea turtle that weighs a ton or more has to consume a lot of jellyfish to keep its energy up. (Photo by Amy Kukulya, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, under NMFS Permit No. 15672-02)

- In addition to jellyfish, sea turtles in Vineyard Sound encounter many obstacles, some of them fatal. Boat strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and consuming plastic bags that they mistake for jellyfish are high on the list, and Dodge hopes that information from TurtleCam will help her better understand the nature of these threats so that she and others can help minimize the danger to threatened species. (Photo courtesy of Amy Kukulya and Kara Dodge, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, under NMFS Permit No. 15672-02)

- A tagged leatherback sea turtle swims at the surface with the REMUS TurtleCam vehicle visible underwater in front of it and a fishing buoy in the background. TurtleCam was originally developed to track and film much different behaviors by white sharks and had to be reprogrammed to follow the yo-yo swimming pattern common to air-breathing marine animals. (Photo by Amy Kukulya, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, under NMFS Permit No. 15672-02)

- Next up, Kukulya and colleague Roger Stokey will fine-tune the programming that controls REMUS TurtleCam in order to increase the amount of time the vehicle can keep a tagged turtle in its field of view. Meanwhile, Dodge will spend her winter combing through hours of footage for insights into the little-seen lives of endangered leatherback sea turtles. (Photo by Ken Kostel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)