Voyage Takes a Census of Life in the Sea

Scientists net a wealth of tiny marine animals, including species never seen before

Scientists collected more than 1,000 shrimplike creatures, swimming snails and worms, and gelatinous animals, including many species never seen before, on a landmark cruise to take inventory of the ocean’s zooplankton.

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution biologist Peter Wiebe led a team of 28 scientists from 14 nations, who used fine-mesh nets to sample from the sea surface to depths of nearly three miles (five kilometers). The April 2006 cruise across the tropical Atlantic Ocean, funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, was part of the Census of Marine Zooplankton (CMarZ) project—an ambitious global effort to assess the kinds, numbers, ranges, and roles of thousands of tiny animals species that provide the link in the marine food chain between marine plant life and predators from fish to whales.

While still at sea, experts in taxomony (the classification of organisms) identified captured species under microscopes while researchers sequenced their genes to create unique DNA “bar codes.” Future scientists will be able to identify species more easily, even if they didn’t study taxonomy themselves.

“Genetic bar codes will be a big step forward,” Wiebe said. “We are trying to provide the stepping-stones so future generations can use the results of this project as a benchmark to measure at a glance how ecosystems are changing in the future.”

The DNA bar codes also reveal genetic variations that allow scientists to differentiate similar-looking species that would otherwise be hard to distinguish by sight, said Ann Bucklin, a University of Connecticut marine scientist who leads CMarZ.

Researchers collected the zooplankton using MOCNESS, or Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sensing Systems, designed by Wiebe and WHOI colleagues. The computer-controlled system allowed scientists to open and close separate nets every 3,000 feet (1,000 meters) throughout the ocean and collect corresponding information about water temperature and salinity. To capture the smallest zooplankton, the nets had a mesh size of 333 micrometers (smaller than the period at the end of this sentence). In addition, scuba divers also collected samples during the day and night.

Slideshow

Slideshow

- Peter Wiebe, senior scientist in the WHOI Biology Department and chief scientist on the Census of Marine Zooplankton cruise, helps launch the Multiple Opening Closing Net Environment Systems Sampler (MOCNESS) from the deck of the NOAA research vessel Ron Brown, to sample ocean life at several depths. The cruise, part of the Census of Marine Life project, brought international experts together to find Atlantic Ocean animal plankton species and identify them using both taxonomic and molecular DNA methods. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- One of the MOCNESS nets rises out of the ocean, with its multiple net ends trailing. Each separate net samples a different ocean depth and is controlled by computer from the ship. (Photo by Ken Buesseler, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- The large MOCNESS, with a 10-meter-square mouth, a heavy metal frame, and nine separate nets, requires many hands to pull aboard after an hours-long tow through the ocean. (Photo by Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- This squid, called Histioteuthis sp., is about six inches long, and lives in the midwater depths, nearly 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) down. Its skin is covered with spots, called chromatophores, that let it change color at will. Interestingly, its two well-developed eyes are two different sizes. (Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

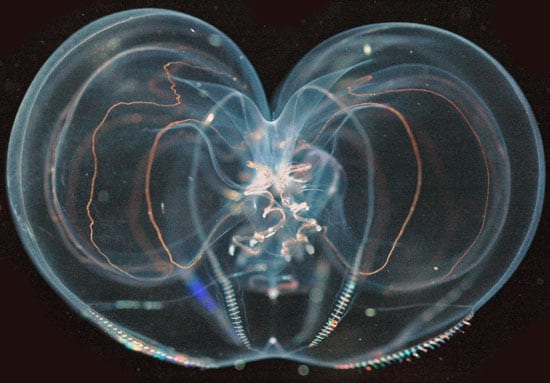

- Deep-living, transparent, and heart-shaped, this ctenophore (or comb-jelly) is called Thalassocalyce, which means "sea chalice." Like all ctenophores, it is predatory, catching prey with sticky secretions. (Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- This rose-tinted shrimplike crustacean, Thysanopoda obtusifrons, is one of the animals known as krill. Krill are a mainstay of the ocean food web, eaten by larger animals including fish, squids, and marine mammals. (Nancy Copley, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

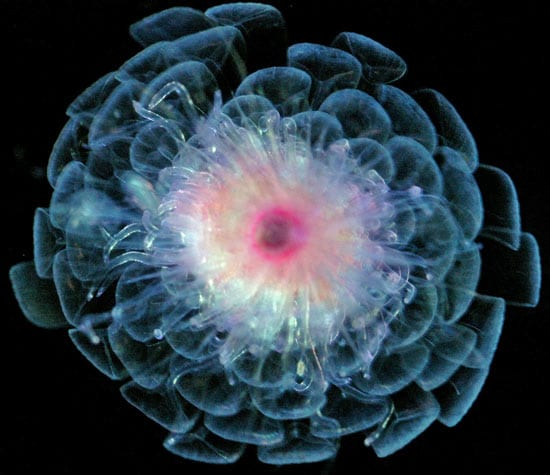

- Looking like a delicate chrysanthemum flower, the siphonophore Athorybia rosacea, a relative of jellyfishes, is actually a carnivorous predator. (Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Alacia valdiviae, an orange ostracod, brought up in the plankton net from deep water. Ostracods are small swimming crustaceans that live within a hinged shell. (Russ Hopcroft, University of Alaska Fairbanks.)

- Radiolarians, single-celled marine organisms that drift in the ocean, live together in large, soft, colonies that can be inches across. An assortment the colonies reveals the variety of shapes they can take. (Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

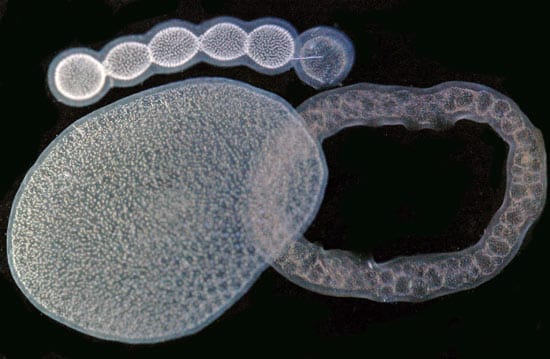

- Pyrosomes are colonial tunicates, animals related to sea squirts, that look like fuzzy paint rollers, with individuals arranged around a hollow tubular center. This one has a spiny single-celled animal called a radiolarian, hitching a ride at one end.

- A copepod from deep in the Atlantic, Valdiviella insignis. Copepods are among the most numerous animals in the sea and are food for many larger animals. (Russ Hopcroft, University of Alaska Fairbanks.)

- A jellyfish-relative called a siphonophore, of the species Rosacea cymbiformis). This one has relaxed and extended some of its many tentacles, which carry batteries of stinging cells to kill prey ranging from plankton to larval and small fish. (Larry Madin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)