Coral Research

- WHOI scientist Konrad Hughen, who studies tropical climate change recorded in coral skeletons, spotted this 15-cm (6-inch) "rosy finger coral" (Stylophora pistillata) at 2-3 meters depth while surveying the health of a Red Sea reef in 2007.

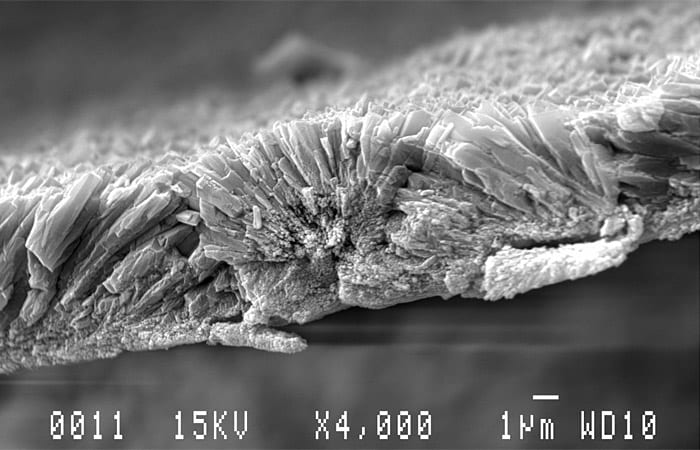

- Seen under a microscope, tiny crystals of aragonite (a form of the mineral calcium carbonate) are carefully organized into a "dissepimental sheet" in the skeleton of a Porites coral. Corals make dissepiments—a type of partitions—at the time of each full moon and use them like rungs on a ladder to support the weight of the coral polyps (individual coral animals) as they keep building new skeleton. WHOI scientist Anne Cohen studies the impact of climate changes, including ocean acidification, on the ability of corals and other marine calcifying organisms to build their calcium carbonate skeletons.

(Photo by Anne Cohen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - MIT/WHOI Joint Program graduate student Kelton McMahon (front) and WHOI research assistant Leah Houghton enter a large underwater cavern on a Red Sea coral reef off Alith, Saudi Arabia in search of adult snapper fish. By analyzing fish otoliths, or ear bones, McMahon can discern where fish spent their formative juvenile years and help identify critical areas that should be protected to prevent the demise of coral reef fish populations.

(Photo by Michael Berumen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - This Red Sea coral reef, located west of Saudi Arabia, is being monitored as part of a collaborative project with King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). Using the data from sensors, and modeling, researchers hope to better understand the mechanisms of water and heat exchange across the boundary of this reef, and similar reefs in the area. Because these reefs have shallow tops, about one meter deep, they tend to become warmer during the day and cooler at the night than the surrounding water. Using the data collected thus far, researchers have found that the water exchange across the reef boundary is generally quite rapid, typically flushing the reef top in about an hour, and is likely driven by a combination of wind and wave driven flows. (Photo by Jim Churchill, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

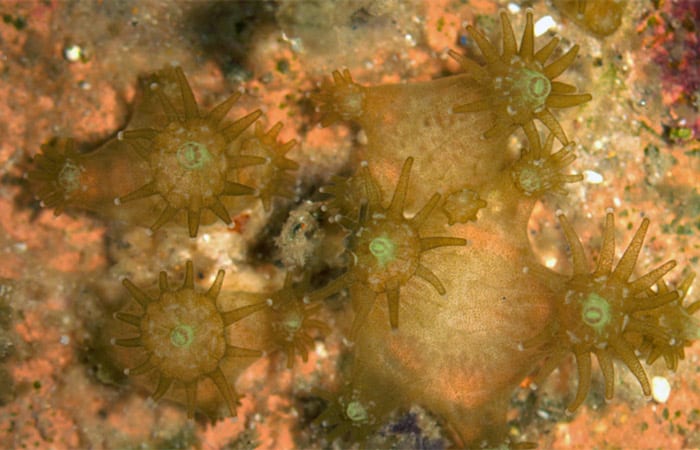

- The Northern Star Coral, or Astrangia poculata, seen here with polyps extended, is a unique cold water coral that occurs in Woods Hole, MA, with (brown) and without (white) symbiotic algae. Both warm and cold-water corals are used at WHOI to research past ocean climate, past ocean circulation changes, and past sea levels. Astrangia poculata colonies are also used in culture experiments to provide insights into coral biomineralization processes and the effects of ocean acidification on calcification. (Photo by Terry Rioux, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Young polyps of the mustard coral, Porites astreoides, extend their tentacles during feeding time at the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences (BIOS). These 12-week old spat, reared from birth in experimental aquaria, are part of a study led by WHOI scientists Anne Cohen, Dan McCorkle and Cabell Davis to investigate the impact of CO2-induced climate change on coral health. (Photo by Kathryn A. Rose and Liz Drenkard, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Dissection of the Red Sea coral Acropora reveals bright pink spheres surrounded by the coral's white skeleton. These are the coral’s eggs. Each individual Acropora makes both eggs and sperm, sticking them together in a bundle that looks something like a soccer ball. All the Acropora on the reef release their bundles at about the same time. Water motion breaks them apart so the sperm can fertilize eggs from other individuals. The fertilized eggs develop into larvae that soon settle onto the reef to begin their lives as coral polyps in the reef community. (Photo by Ann Tarrant, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

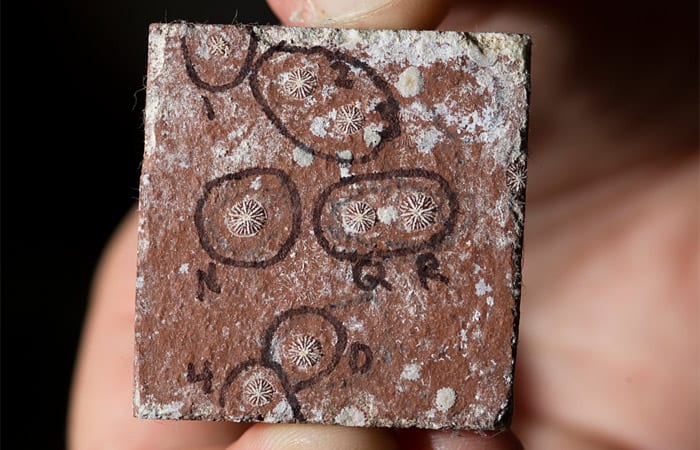

- Summer intern Hannah Barkley holds a ceramic tile on which several star-shaped skeletons of newly-settled coral have developed (circled). A senior at Princeton, Barkley spent the summer working with WHOI scientist Anne Cohen and Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences (BIOS) scientist Samantha de Putron. Barkley spent six weeks at BIOS collecting and rearing baby corals under different conditions of food and temperature. Back at WHOI, she quantified the impacts of the conditions on amount of skeleton the corals produced. (Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Gliding over a Bermudan coral reef in October 2010, WHOI scientist Anne Cohen (center) and post-doctoral investigator Neal Cantin (left) were followed by a BBC cameraman. The group was filming a segment for a BBC documentary called "Do We Really Need the Moon?” focusing on the influence of the moon on corals and coral reefs. They were attempting to describe how coral feeding and spawning patterns are strongly linked with lunar cycles, as well as showing the microscopic structures in coral skeleton that are formed during a full moon.

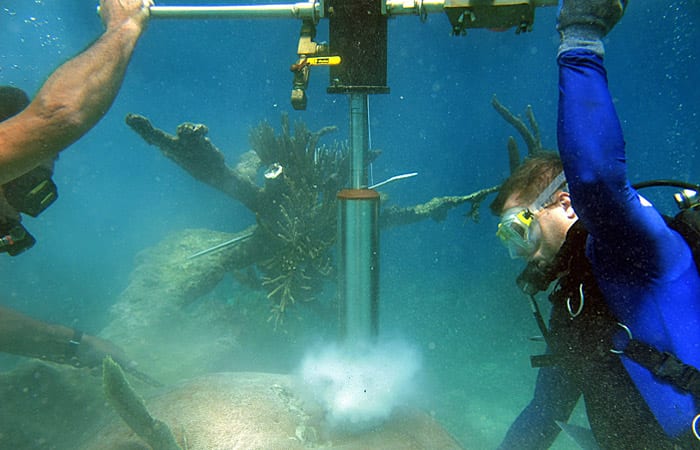

(Photo by Alex Chequer, Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences) - WHOI scientists Pat Lohmann (left) and Neal Cantin drill into a massive starlet coral on a reef north of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, to remove a core sample. The core provides information about changing ocean conditions and how the coral responded to those changes over the last few hundred years. After the core is removed, the divers plug the drill hole with cement to prevent infection. The coral is fully recovered within a year. (Photo courtesy of Anne Cohen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

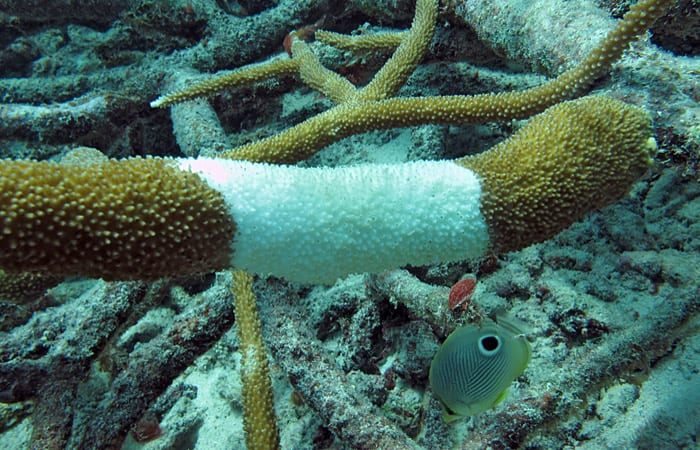

- A staghorn coral branch (Acropora cervicornis) on a reef west of St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, suffers from White Band Syndrome, a coral disease that has been a significant source of coral mortality throughout the Caribbean region. Coral diseases and bleaching events have increased since the 1980s due to human impacts to water quality and climate change. WHOI scientists Anne Cohen, Delia Oppo and Neal Cantin have been collecting coral cores from this region to investigate how corals are responding to changing ocean conditions, particularly temperature, over the last few hundred years. (Photo by Neal Cantin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- What seems like a fractal landscape of mountains and canyons is actually a "corrugated coral," a reef-building species with a hard skeleton, photographed under a microscope. Pockets of tiny white threads on the coral, which is feeding on tiny swimming animals, are digestive, "mesenterial," filaments the coral polyps extrude to snare and digest prey. The coral was collected in Panama during the MIT-WHOI Joint Program's January, 2011 Field Course in Tropical Marine Ecology at the Liquid Jungle Lab, taught by WHOI biologists Jesús Pineda and Ann Tarrant.

(Photo by Liz Drenkard, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) - A pink anemonefish (Amphiprion perideraion) looks out from the tentacles of its home, a big anemone in Kimbe Bay, Papua New Guinea, where WHOI fish ecologist Simon Thorrold has a long-term research project to study connections among populations of reef fish. Thorrold tracks the migrations and dispersal of fish, ranging from this small reef-dweller to whale sharks, the largest fish in the sea. (Photo by Simon Thorrold, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Can you spot the pygmy seahorse (Hippocampus sp.)? (Hint: Its head is pointing back and to the left, with its left eye partly visible.) This little fellow, about a quarter of an inch long, clings to a stem of a gorgonian coral with its prehensile tail. Its color and the bumps on its body make it resemble the knobby host. WHOI biologist Simon Thorrold found it along a coral reef in Kimbe Bay on the north side of the island of New Britain, Papua New Guinea. He traveled there recently to study the movement of eggs and larvae of coral reef fishes among marine protected areas within the bay. (Photo by Simon Thorrold, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- Using SCUBA gear so she can remain submerged, Joint Program student Hannah Barkley drills into a coral colony in Palau to extract a core sample of the skeleton. Analyzing the coral skeleton will reveal the coral's response to ocean warming. Barkley, a graduate student in biologist Anne Cohen's lab, spent ten days studying Palau's coral reefs, collecting seawater and coral samples, to examine the impacts of global warming and ocean acidification on the island nation's reef ecosystem. (Photo by Alexi Shalapyonok, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

- WHOI research assistant Justin Ossolinski snorkels over a massive coral in Vietnam--the largest of its kind in the country, according to WHOI climate scientist Konrad Hughen's colleagues at the Institute of Oceanography in Nha Trang, Vietnam. Hughen and Ossolinski visited Vietnam in 2010 to sample coral skeletons, which Hughen uses to reconstruct past climate. The skeleton composition reflects climate conditions during the coral's lifetime, and the bigger the coral, the longer its climate record. Hughen estimates this coral to be more than 450 years old, and the researchers named it "To Nhat," meaning "big one" in Vietnamese. (Photo by Konrad Hughen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

TOPICS: Corals

Image and Visual Licensing

WHOI copyright digital assets (stills and video) contained on this website can be licensed for non-commercial use upon request and approval. Please contact WHOI Digital Assets at images@whoi.edu or (508) 289-2647.