WHOI Team Aids Center for Coastal Studies in Whale Disentanglement

May 6, 2009

On Monday, May 4, a team of researchers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) was working in the Great South Channel 40 miles east-southeast of Chatham, Mass., when they sighted a humpback whale severely entangled in fishing gear. They alerted a rescue team from the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies (PCCS) and kept watch over the humpback for three hours until the PCCS team could steam to the area to free the whale.

The researchers, led by WHOI biologist Mark Baumgartner and working aboard the Institution’s coastal research vessel Tioga, were in the area studying the feeding behavior of the endangered North Atlantic Right Whale when, around 11:15 a.m., they first spotted the distressed humpback.

“We were looking for right whales when we caught a short glimpse of a fluke up in front of us. We stopped the boat and waited for the animal to resurface,” said Baumgartner. “When it did, we saw it was a humpback, and then we saw a green and white buoy following the whale – it was attached and we knew the animal was entangled.”

The team on Tioga, which included four other researchers, the captain and a mate, noticed a line cutting into the animal’s back and a large mass of tangled rope and buoys along its left flank. They watched as it moved slowly to the north, taking dives that lasted two or three minutes, and contacted the large whale disentanglement team at PCCS, providing their location and a detailed description of the entanglement. The PCCS team determined it would take several hours to reach the area and asked Tioga if it could stand by the whale until rescuers could reach the site.

To hasten the PCCS team’s arrival, the Tioga offered to provide the fuel their ship would need for its return trip and to provide a small boat for their use on the scene.

“That probably saved about two hours, and we knew time would be important,” said Baumgartner. “We knew the weather for the next four or five days was going to be rough and that this was the best chance the PCCS team would have to remove the gear from this animal.”

Baumgartner also knew it was the last good weather day his team would have for its own research for some time. “When I saw the animal, I have to say I was disappointed. We had high hopes of finding and studying right whales that day, and we knew this entangled animal was the end of our research day. But once we saw those ropes around the animal, helping out was clearly the right thing for us to do, so that’s what we did.”

While it waited over the next three hours for the PCCS ship to arrive, the Tioga followed the whale as it slowly moved northward, three or four miles from where it was first spotted, and the researchers provided updates to the PCCS team underway aboard the Ibis.

At approximately 2:15, the Ibis rendezvoused with Tioga.

“If they hadn’t stood by it we never would have re-found it,” said Scott Landry, director of the PCCS entanglement response program, who along with Brian Sharp led the disentanglement effort. “Entangled animals tend to be very low-profile and in the vastness of the ocean, it’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

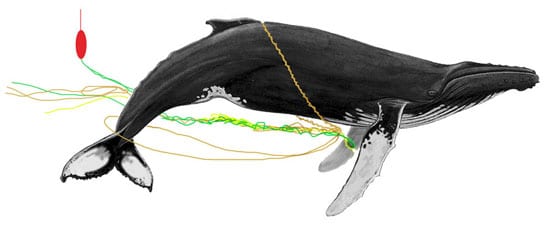

Upon arriving, the PCCS team attached a work line to the whale’s entanglement using a thrown grappling hook. The team then boarded the Tioga’s inflatable boat to examine the whale and the extent of the entanglement. Landry and Sharp determined that the whale had 12-15 wraps of line midway down the left flipper that led to a tangle of line alongside the flank. The wraps had cut deeply through the flipper. Two lines from the tangle twisted together and wrapped around the body, just forward of the dorsal fin. Another loop of line was loosely wrapped around the tail.

Landry and Sharp attached a series of buoys to the work line to slow the animal down and prevent it from diving, then sidled up to the whale. Over the next hour they methodically removed the line from the animal, first from the animal’s back and the tail, and finally from its flipper.

“All of us were amazed at how quickly and calmly they worked. They did it as professionally and as calmly as could be,” said Baumgartner. “Realistically, with one slash of the animal’s tail, the whale could have capsized their boat or killed these guys. It was amazing the animal laid still and let them cut the gear off.”

The line wrapped around the whale’s flipper presented more of a challenge because the rope had cut through to the bones of its flipper and the injuries were severe. For that operation, Landry and Sharp donned snorkeling masks and peered overboard so they could see where they would make cuts around the flipper on the whale’s underside.

After an hour of working away at the lines, Landry and Sharp made just the right cuts so that when the animal swam forward, the gear came away. The animal swam off and about eight minutes later it resurfaced over a half mile away.

“When the humpback swam away, I felt relief. Relieved that the whale was free of gear and that the PCCS team was safe,” recalls Baumgartner. “After that, it just felt good. Like we had helped out a little.”

The team from PCCS removed hundreds of feet of different types of ropes and buoys from the animal, and estimates that the gear had been attached to the humpback for some time and would have likely lead to death.

“It was an incredible relief to remove all of that gear,” said Landry. “Not only was the operation finished without any human injury, but also it seemed apparent that within hours or days that whale would start to feel much better without the constant rubbing of rope in open wounds.”

While entanglements are pervasive in humpback and right whales—both endangered species—relatively few entangled whales are found, leaving many to carry fishing gear around for months or even years. Of the approximately 900 whales in the Gulf of Maine humpback whale population, more than half have experienced an entanglement in their lifetime and 8-25 percent acquire new entanglement scars annually. Less than 10 percent of humpback whale entanglements are actually witnessed and reported, highlighting the special effort of the Tioga for this whale.

According to the PCCS humpback whale program, the humpback whale saved on Monday is approximately 14 months old and was last seen in September 2008 as a calf alongside its mother “Ravine.” Ironically, Ravine was also involved in a serious entanglement in 2003.

“I have to admit that the operation took on a whole new light when the humpback whale studies program informed us that the whale was the offspring of Ravine,” said Landry. “We disentangled Ravine in 2003. Her entanglement was nasty and the disentanglement was especially hard-won. The whale we disentangled on Monday was Ravine’s first documented calf after her disentanglement.”

This year, five unique cases of humpback entanglements have been reported. Three have been successfully disentangled, the other two are still at large because the people who spotted them couldn’t stand by the whale until rescuers arrived. These two entangled whales have not been sighted since.

Major support and permitting for disentanglement efforts comes from NOAA. Mark Baumgartner’s right whale feeding study is supported by the Office of Naval Research and NOAA.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution is a private, independent organization in Falmouth, Mass., dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930 on a recommendation from the National Academy of Sciences, its primary mission is to understand the oceans and their interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate a basic understanding of the oceans’ role in the changing global environment.

The Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies maintains an on-call fulltime primary response disentanglement team on Cape Cod that is prepared to travel as needed throughout the entire Atlantic Coast of the United States. PCCS also provides response coordination and technical services such as equipment development and distribution, satellite telemetry, and data management. PCCS works closely with NOAA to respond to reports of entangled whales and operates under a federal permit to disentangle marine animals. NOAA authorizes disentanglement activities in the United States. To report an entanglement, please call the PCCS Marine Animal Entanglement Hotline, 1 800-900-3622.