Introduction to the Indian Ocean

Hood, R. R., Ummenhofer, C. C., Phillips, H. E., & Sprintall, J. (2024). Introduction to the Indian Ocean. In C. C. Ummenhofer & R. R. Hood (Eds.), The Indian Ocean and its Role in the Global Climate System (pp. 1–31). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822698-8.00015-9

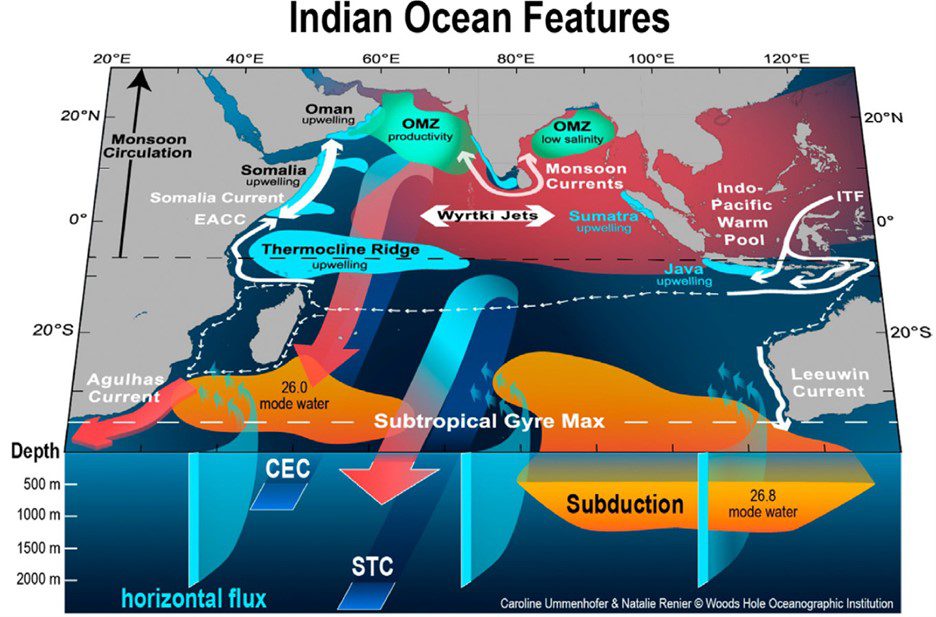

Indian Ocean main oceanographic features and phenomena. The surface circulation seasonally reverses north of 10°S under the influence of monsoons. The summer monsoon also promotes the intense Somali current as well as upwelling and high productivity in the western Arabian Sea. High surface layer productivity, sinking of biomass, and its remineralization at depth also lead to the formation of subsurface oxygen minimum zones (OMZs) in the Arabian Sea and Bay of Bengal. The Indo-Pacific warm pool is a region of intense air-sea interactions, where the Madden-Julian oscillation, monsoon intraseasonal oscillation, and Indian Ocean dipole develop. The Indian Ocean is a gateway of the global oceanic circulation, with inputs of heat and freshwater through the Indonesian Throughflow, which exit the basin though boundary currents, mainly the Agulhas Current along Africa, but also the Leeuwin Current along Australia. There are two vertical overturning cells connecting subducted waters south of 30°S to the tropical Indian Ocean: the shallow subtropical overturning cell where water upwells in the “thermocline ridge” open-ocean upwelling region, and the cross-equatorial cell where water upwells farther north in the Arabian Sea of the coast of Somalia and Oman. These cells are the main source of subsurface ventilation due to the presence of continents to the north. (Figure reproduced from Hood et al., 2024)

This chapter provides an overview of the research history, geology, and physical and biogeochemical variability in the Indian Ocean. A major theme that emerges from this book, is that there is a very strong link between atmospheric forcing and physical, biogeochemical, and ecological responses in the Indian Ocean, as observed everywhere in the global ocean. However, the Indian Ocean is unique in that the atmospheric forcing due to the monsoon winds is particularly strong and periodic. The low-latitude land boundary to the north and the tropical connectivity to the Pacific in the east via the Indonesian Throughflow further make it distinct. The Indian Ocean also has remarkably complex bottom topography. These attributes combine to give rise to circulation patterns and physical variability that are not seen in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, which, in turn, give rise to strong and unusual biogeochemical and ecological responses. For example: 1) the South Asian monsoon represents the largest monsoon system on Earth, the Indian Ocean has the world’s largest southward meridional heat transport, and the Indian Ocean is characterized by unusually active intraseasonal variability; 2) the Arabian Sea has the thickest oxygen minimum zone in the world and some of the lowest pH values in the world have been measured in surface waters of the Indian Ocean; and 3) tuna catches in the Indian Ocean represent a large fraction of the world tuna and billfish catch, with 90% of the neritic tunas caught by the coastal/artisanal fisheries. All of this makes the Indian Ocean a fascinating place for atmospheric and oceanographic study where many important research questions still remain unanswered.