Oil Spills

Deep Water Horizon. (Cabell Davis, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

What is an oil spill?

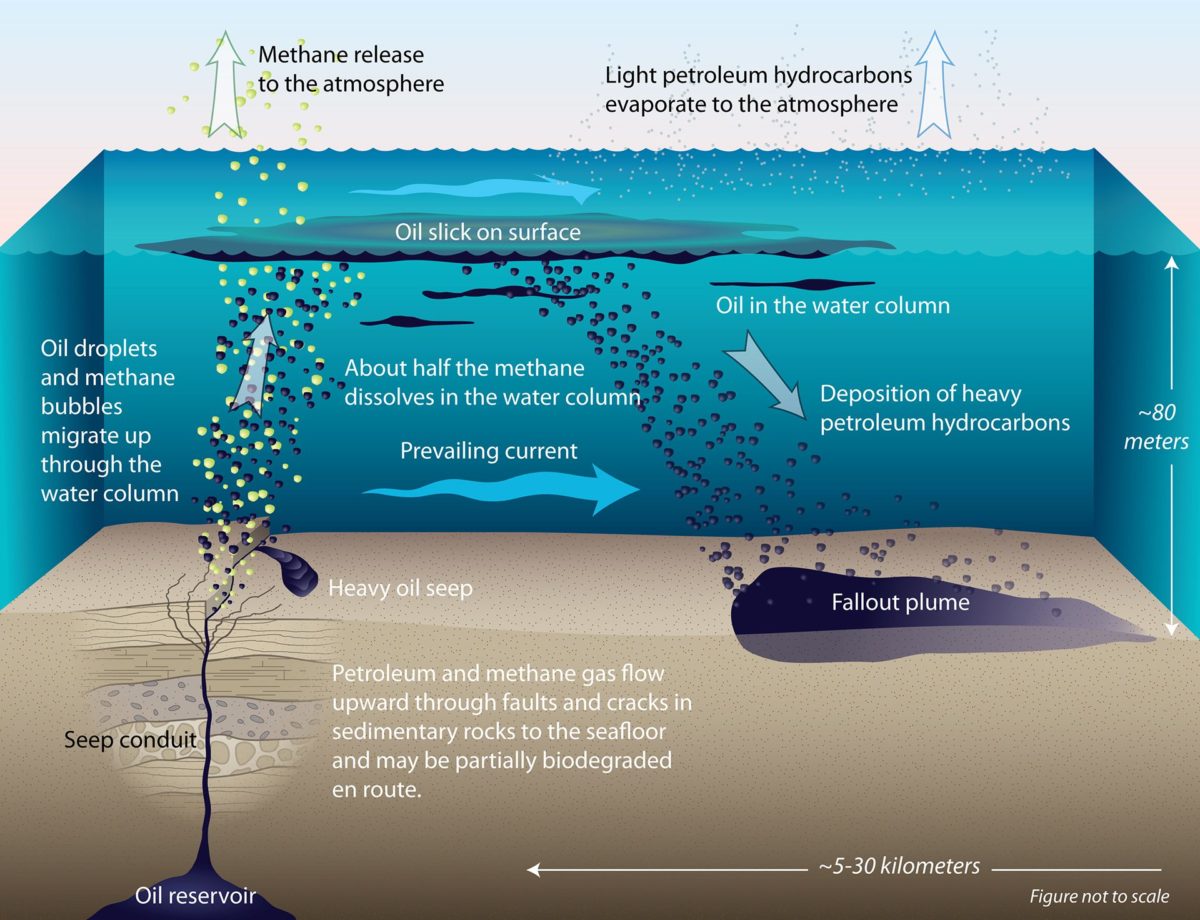

Millions of years ago, sediment buried dead plants and animals. After that, high pressure and temperature conditions caused them to decay into a liquid form — oil — below ground. Today we tap into these oil pockets to generate power and fuel global transportation. Although oil originated with living organisms, its current form causes harm when it spills into the environment. To complicate matters, oil is a complex cocktail of tens to hundreds of thousands of compounds that behave in different ways when they interact with the ocean environment.

Oil spills happen regularly. Most are small, but some can be massive, releasing millions of gallons of oil into the ocean. When spills happen — whether they are near the coastline or offshore — wind, waves, and currents can carry the oil to shore, where it contaminates everything it touches.

What causes these types of spills?

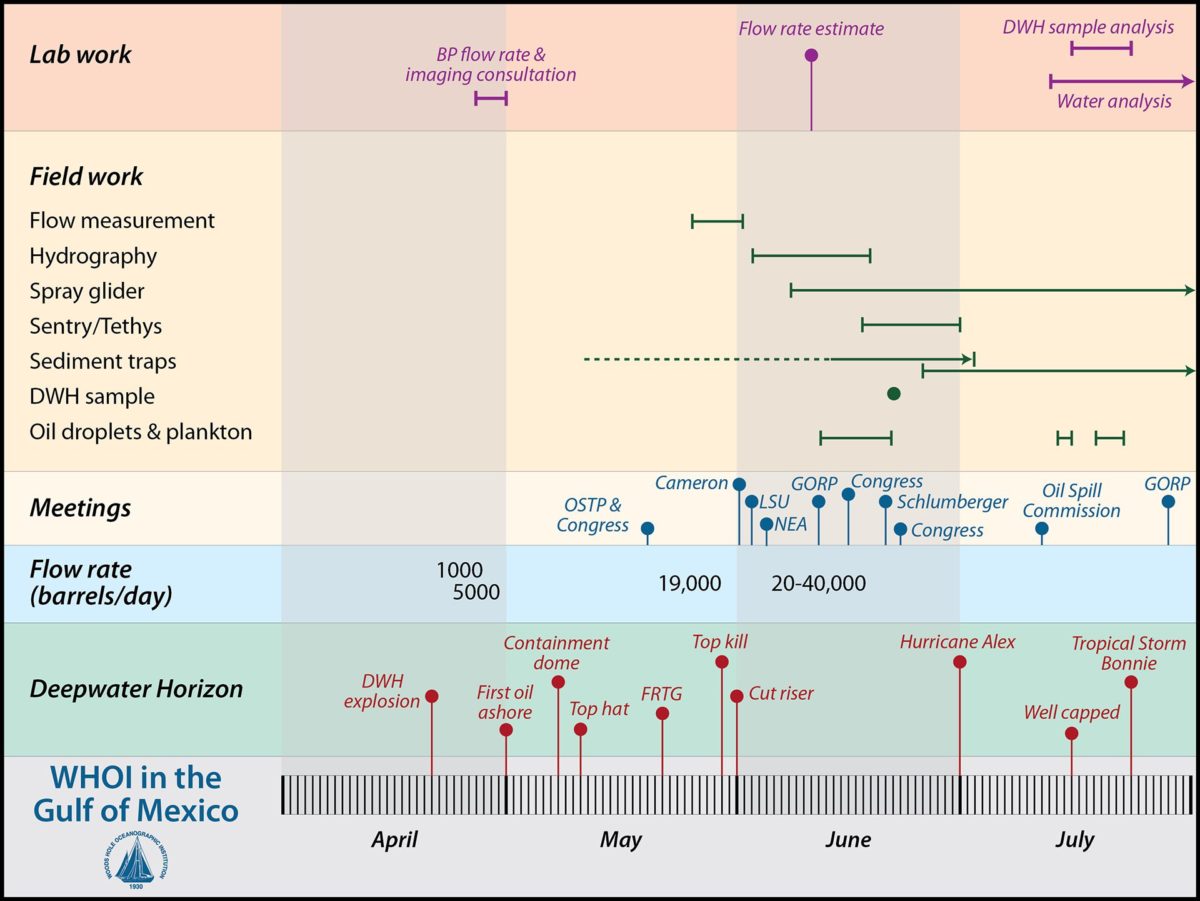

The majority of oil spills, such as those that occur while refueling ships, are too small to garner much public attention. Larger spills occur when tankers collide or run aground on reefs and begin to leak their contents into the water. For example, a grounding event caused the Exxon Valdez spill off the coast of Alaska in 1989, releasing 11 million gallons of oil to the Gulf of Alaska. The largest spill in U.S. history, Deepwater Horizon in 2010, occurred when an offshore oil rig exploded and later collapsed. The damaged well ultimately spewed 134 million gallons of oil and gas into the Gulf of Mexico — the equivalent of more than 200 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

What kind of impact do oil spills have?

The most obvious impact on the environment is when large animals become oiled. As birds, sea turtles, and marine mammals swim through the oil slick, their bodies become coated. That oil prevents birds and mammals from staying warm, and as they are exposed to cold temperatures, they can easily die.

Another impact is when smaller organisms are coated in or ingest oil. Both methods of exposure can cause illness, behavioral changes, and even death due to a variety of toxic chemicals. Some of the smallest organisms may experience the highest mortality rates. For instance, plankton includes tiny, free-floating larvae of many organisms, from corals to mollusks to crabs. When plankton is exposed to oil during the larval stage, this can lead to physical and behavioral abnormalities that later affect adult populations.

On the human side, oil spills have extremely harmful impacts on public health. People can be exposed to toxic chemicals when they visit a contaminated beach, consume contaminated seafood, or inhale airborne chemicals released by a nearby spill. Common symptoms include dizziness, headaches, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue. Over time, people may experience immune system, endocrine, or cardiovascular problems or develop cancer.

Mental health also suffers. As oil spills damage property and people lose jobs, stress levels increase, along with anxiety, depression, and thoughts of suicide. Rates of domestic violence increase. Communities may experience loss of local industries, particularly fisheries, recreational fishing, and tourism. In extreme cases, entire communities may need to relocate.

How can we detect and respond to oil spills?

A variety of remote sensing (plane and satellite) techniques can detect and track oil spills. Remote sensing instruments detect variations in the ocean’s surface to identify areas with oil and those without. Once an instrument detects a spill, it must be contained quickly, particularly if it occurs near sensitive marine ecosystems, such as coral reefs, estuaries, seagrass meadows, and mangrove forests. Because low tide brings oil slicks in contact with organisms in shallow areas, emergency responders often attempt to prevent oil from reaching shore and near-shore areas. However, doing so requires fighting against wind and wave actions that carry oil onto land.

Response teams can corral slicks using booms to prevent the oil from reaching sensitive areas. Once it is contained, skimmers remove the oil from the water’s surface. When large quantities of oil contaminate the ocean, as happened with the Deepwater Horizon event, burning may be in order. Response teams use fire-proof booms to gather the oil before lighting it on fire to prevent its spread. They can also burn oil that has reached land to help vegetation recover more quickly.

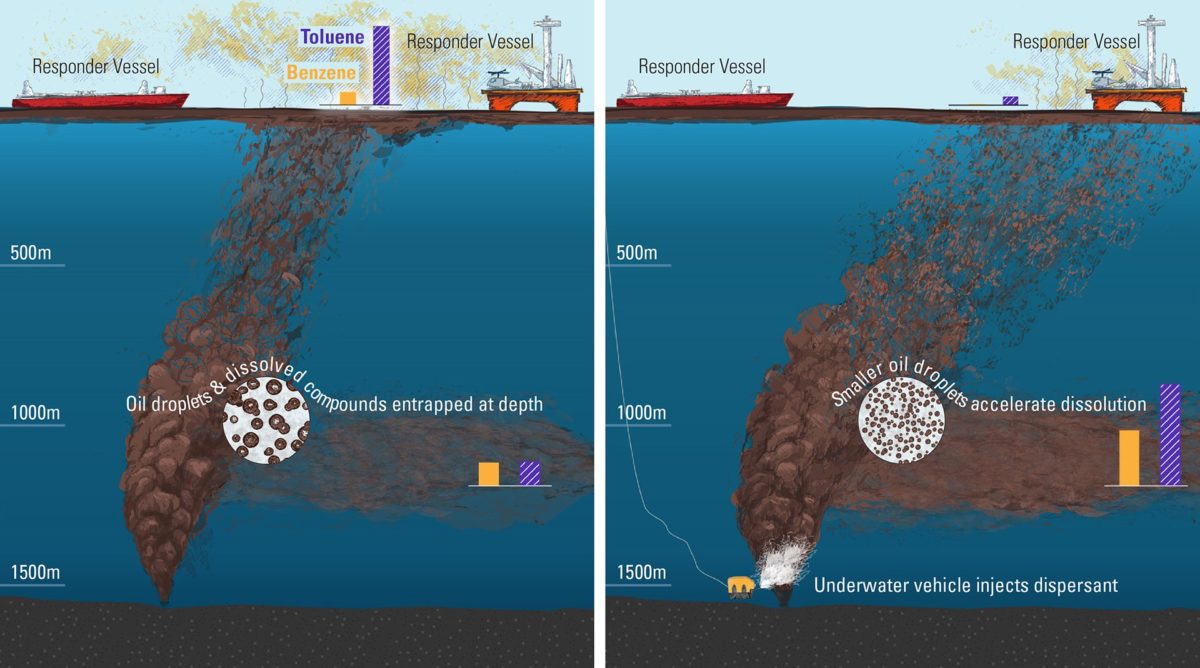

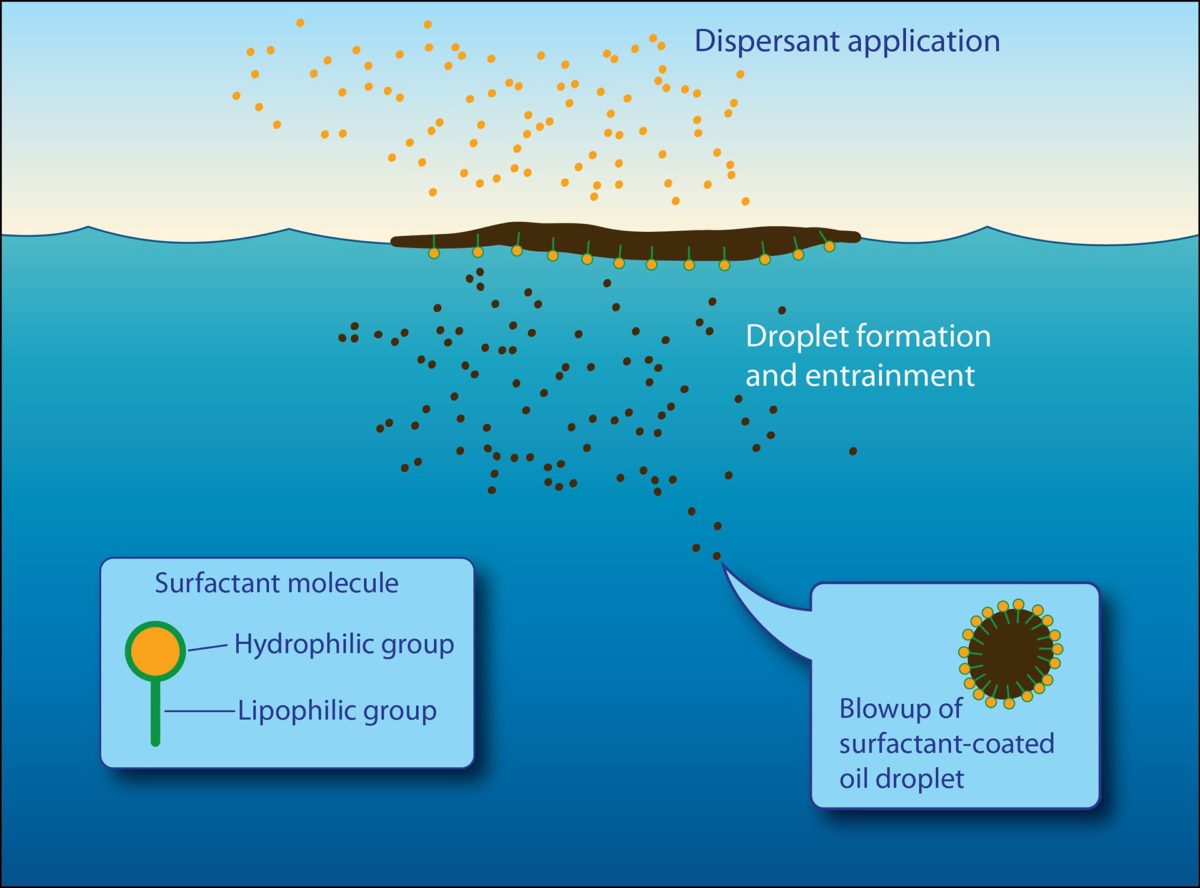

Over time, naturally occurring microbial communities break down the oil in the ocean in a process called bioremediation. Under the right conditions, dispersants can help break a larger oil slick into smaller droplets. This increases the surface area of the oil, providing microbes with greater access to the rich source of carbon contained within. Once oil has reached shore, responders use surface washing agents, such as dishwashing soap, to remove it from surfaces.

How do scientists study oil spill events?

Scientists track and model oil spills to enhance response time and decrease damage to the ocean ecosystem. Additionally, toxicologists are investigating the health effects of exposure to oil. Most studies of oil spills have focused on individual species, but some researchers are beginning to examine the ecosystem-wide effects of these disasters.

Asif, Z. et al. Environmental impacts and challenges associated with oil spills on shorelines. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. Vol. 10. May 31, 2022. doi: 10.3390/jmse10060762

Hu, C. et al. Optical remote sensing of oil spills in the ocean: What is really possible? Journal of Remote Sensing. Vol. 2021. February 13, 2021. doi: 10.34133/2021/9141902

Michel, J. Oil Spill Task Force. Surface Washing Agents. https://oilspilltaskforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/SurfaceWashingAgents.pdf

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Oil in the Sea IV: Inputs, Fates, and Effects. 2022. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/26410/oil-in-the-sea-iv-inputs-fates-and-effects

NOAA. What happened during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill? https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/education/tutorial-coastal/oil-spills/os04-sub-01.html

NOAA Office of Response and Restoration. How Do Oil Spills out at Sea Typically Get Cleaned Up? https://response.restoration.noaa.gov/about/media/how-do-oil-spills-out-sea-typically-get-cleaned.html

Soares, M.O. & E.F. Rabelo. Severe ecological impacts caused by one of the worst orphan oil spills worldwide. Marine Environmental Research. Vol. 187. March 7, 2023. doi: 10.1013/j.marenvres.2023.105936

Ward, C. The sun’s overlooked impact on oil spills. Oceanus. December 19, 2018. https://www.whoi.edu/oceanus/feature/the-suns-overlooked-impact-on-oil-spills/

Ward, C., personal communication.

Oil in the Ocean

The systematic study of oil in the ocean is relatively new to science, but since the late 1960s it has grown to encompass almost every area of oceanography.

Because oil is not a single substance, scientists face a number of challenges when it enters an environment as complex as the ocean. Crude oil and many refined petroleum products are a complex mixture of hundreds of chemicals, each one with a distinct set of behaviors and potential effects when released into the marine environment. Some of these substances differ only in the location or orientation of a single carbon atom on a long molecular chain involving dozens of atoms.

Despite this, even chemicals with nearly the same molecular structure can behave very differently once they enter the water, atmosphere, sediments, or an organism. As a result, scientists who study oil in marine settings often say that every spill is different and find that they must ask a unique set of questions every time they focus on a new location or event.

News & Insights

What happens to natural gas in the ocean?

WHOI marine chemist Chris Reddy weighs in on a methane leak in the Baltic Sea

Forged in fire: WHOI recalls the Deepwater Horizon crisis

It’s been a decade since the explosion of the BP oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico. Frontline WHOI scientists face unprecedented challenges when called to respond to the largest accidental oil spill in history.

Fifty years later, the West Falmouth oil spill yields lasting contributions to remediation efforts

After 175,000 gallons of oil spilled from a barge that ran aground along West Falmouth Harbor, the contaminant has all but disappeared, save a small marsh inlet that continues to serve as a living laboratory for scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Rapid Response at Sea

As sea ice continues to melt in the Arctic and oil exploration expands in the region, the possibility of an oil spill occurring under ice is higher than ever. To help first responders cope with oil trapped under ice, ocean engineers are developing undersea vehicles that can map oil spills to improve situational awareness and decision making during an emergency.

Five Years After Deepwater Horizon: Improvements and Challenges in Prevention and Response

April 29, 2015 Christopher M. Reddy, Ph.D., Senior Scientist, Marine Chemistry & Geochemistry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution April 29, 2014—U.S. Senate Committee on Science, Commerce & Transportation Salutation Chairman Thune…

News Releases

Dissolving oil in a sunlit sea

What did scientists learn from Deepwater Horizon?

[ ALL ]

WHOI in the News

How do we deal with oil spills in the future?

Oil is more likely to stick around in a cold, sunny ocean

[ ALL ]

From Oceanus Magazine

The ocean currents behind Brazil’s pollution problem

South America’s largest country reckons with both history and ocean currents in a recent spree of pollution

Sunlight and the fate of oil at sea

Danielle Haas Freeman draws on the language of chemistry to solve an oil spill puzzle

A toxic double whammy for sea anemones

Exposure to both oil and sunlight can be harmful to sea anemones

WHOI scientists discuss the chemistry behind Sri Lanka’s flaming plastic spill

Eight months after the M/V X-Press Pearl disaster in Sri Lanka, WHOI investigators talk about their research on the unique chemistry of the spilled plastic nurdles

Oil spill response beneath the ice

Successful test deployment of WHOI vehicle Polaris expands U.S. Coast Guard response to oil spills in the Arctic

Beach Closures

Beach Closures  Marine Microplastics

Marine Microplastics  Radiation

Radiation