Coral Stressors

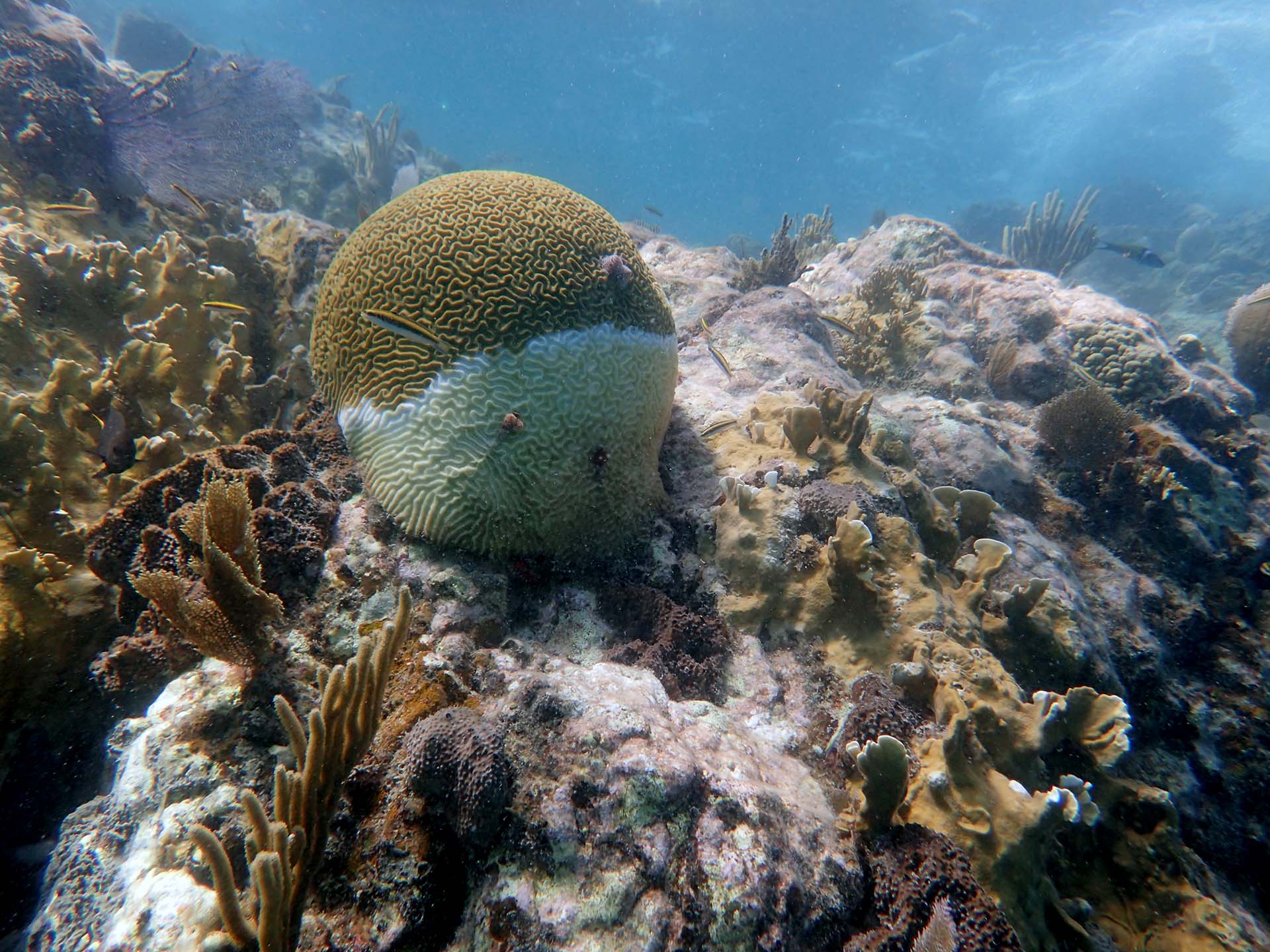

Evidence of coral bleaching along the U.S. Virgin Islands. Courtesy of Amy Apprill, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

What are coral stressors?

Coral reefs are some of the world’s most spectacular ecosystems. Bright fishes dart among colorful corals dotted with a wide variety of other organisms. But these ecosystems are struggling around the globe, thanks to a number of stressors. By itself, a single stressor can cause damage to corals and other organisms that depend on the reefs corals build, but in many cases, these reefs face a number of simultaneous threats that make recovery a much bigger challenge.

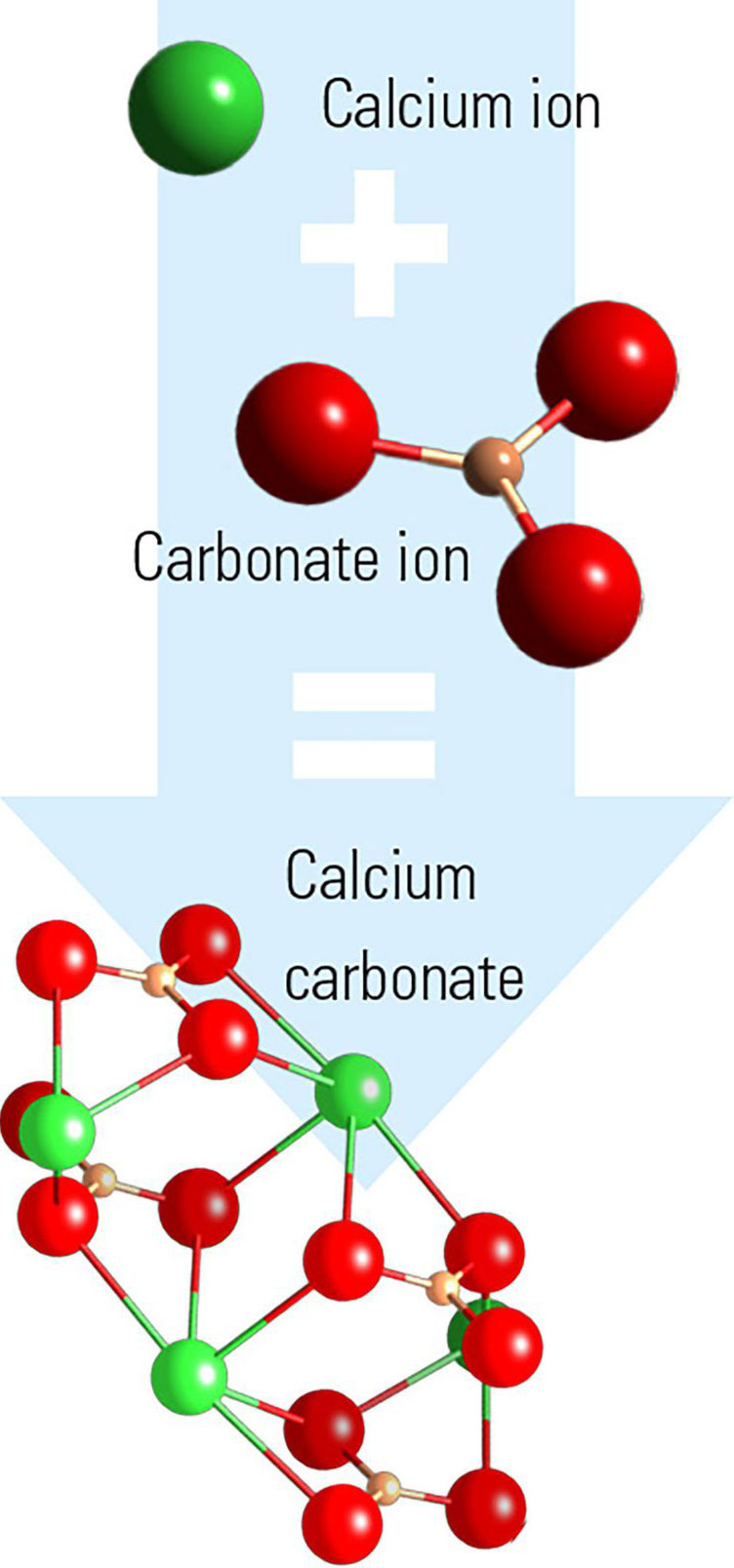

Corals make up the backbone of these reef ecosystems. Tiny animals called polyps secrete a calcium carbonate skeleton they use for support and protection. This rock-like skeletal structure is what we often think of as coral, but the coral in a reef is alive and growing, adding new layers to the skeleton over time. As the skeletal structures grow, they create the three-dimensional habitat that makes up a reef. Nooks and crannies offer habitat for fishes and other animals. The solid foundation slows waves and provides a place for stationary organisms to anchor.

Stressors can affect organisms living on the reef or they can affect the corals, themselves. When corals die, other organisms must relocate or struggle to survive. Stressors the world over stem from human activity.

What stressors affect corals globally?

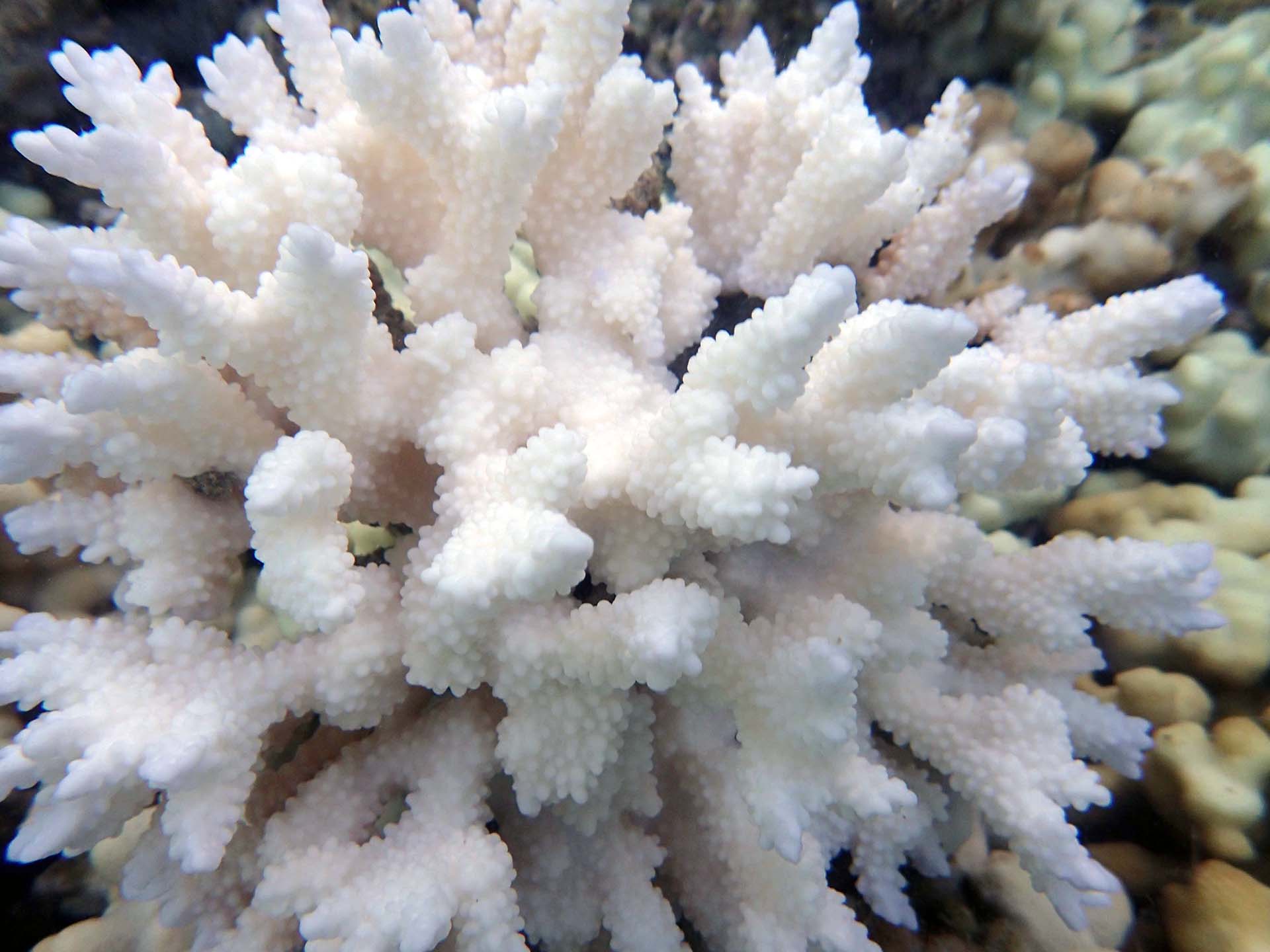

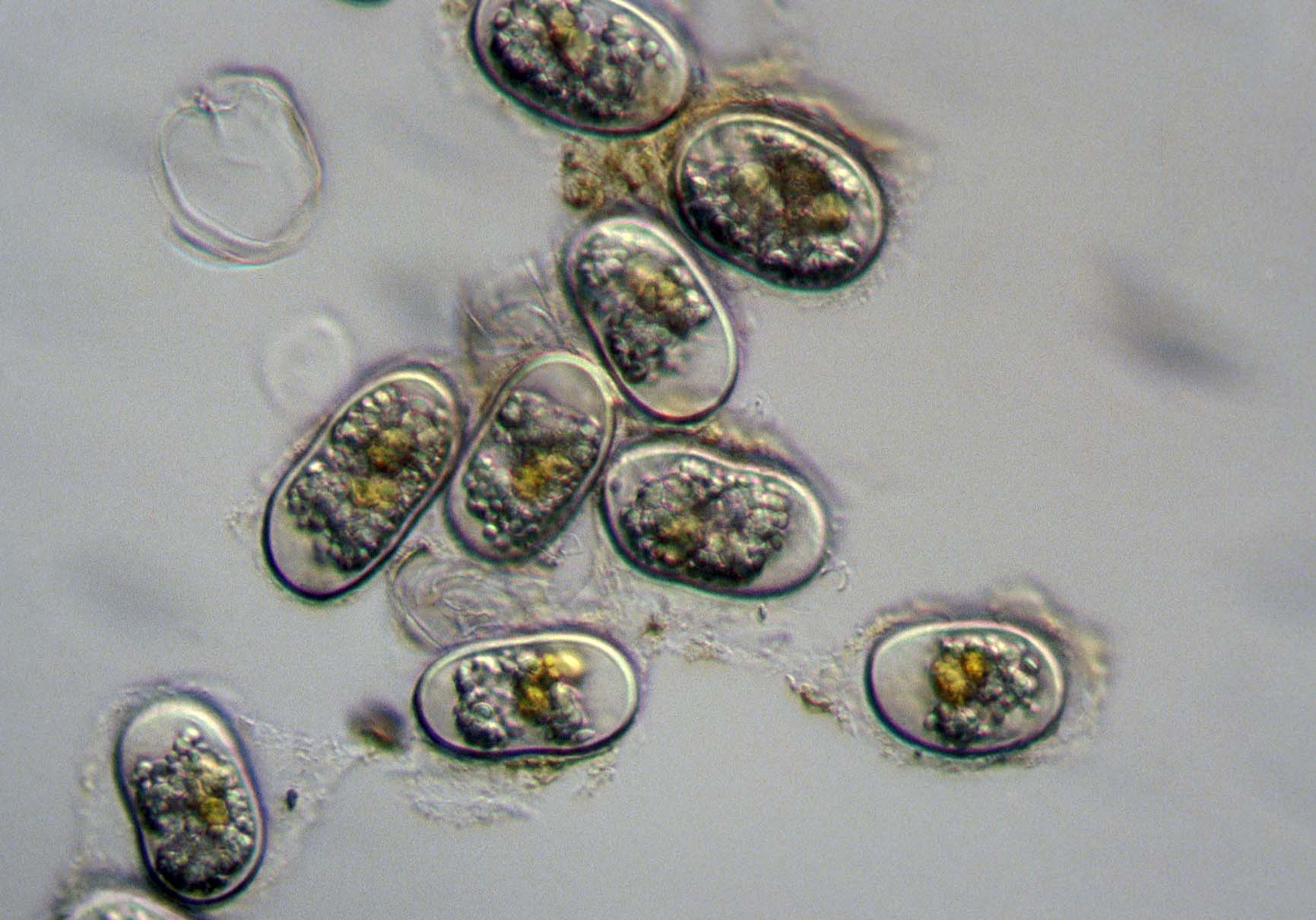

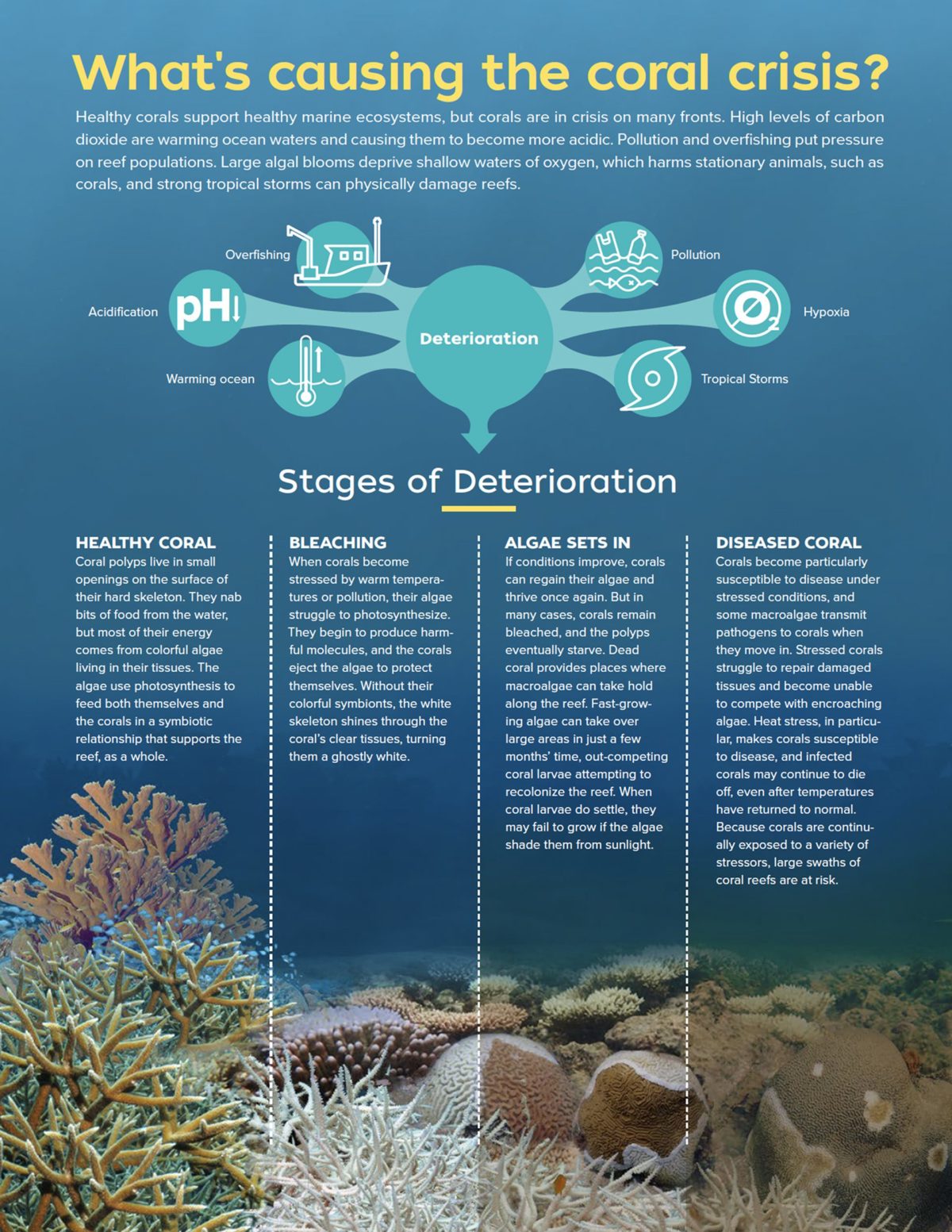

On a global level, coral reefs are threatened by climate change. Warming water temperatures can cause corals to eject tiny symbiotic algae from their tissues in an event called bleaching. These algae provide most of corals’ nutrients, and corals that have bleached eventually starve if temperatures don’t return to normal levels and the algae repopulate the polyps.

The high levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide driving current warming are also problematic, as ocean waters absorb the gas and it reacts with seawater. The result is carbonic acid, which reacts with carbonate, such as that found in coral skeletons. Over time, ocean acidification has weakened coral skeletons in a manner similar to osteoporosis affecting human bones. Skeletons become more likely to erode from wave action or break apart during big storms, which are becoming more frequent and intense because of climate change.

Global levels of carbon dioxide aren’t the only reason for acidification. A recent study by WHOI scientists found that reefs in areas near land that are affected by runoff, pollution, and overfishing were more likely to show signs of damage from acidification. Reefs in more remote areas, on the other hand, fared better despite rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and increasing global temperatures.

What stressors are more local?

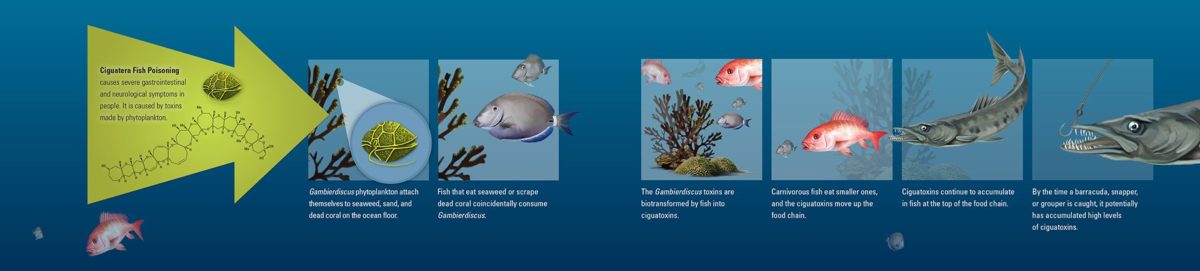

Runoff from land contributes to other problems for coral reefs. Runoff often carries with it pollutants from the mainland: fertilizers and pesticides from agricultural and urban land use, sediment and toxic chemicals from coastal development and road construction, and pathogens from sewage and other stormwater runoff. Toxic chemicals, including pesticides, can directly harm organisms living on the reef. Fertilizers, which may seem innocuous, can be extremely damaging if they trigger an algal bloom. When large numbers of algae—even tiny phytoplankton—grow to excess, they block sunlight from reaching the corals below. Without sunlight, those corals and their symbiotic algae get insufficient food. This can weaken the corals and make them more susceptible to disease. Sediment similarly creates murky waters that can block photosynthesis.

Algal blooms can cause damage in other ways. Some algae release toxins; when these algae occur in large numbers, we get a harmful algal bloom that sickens wildlife and even people. And when the algae die and sink, decomposition uses up oxygen in the water, which can suffocate oxygen-breathing organisms, including fish, crustaceans, sea stars, bivalves, and more. Under normal circumstances, mixing of surface waters with deeper layers prevents such extreme low-oxygen conditions, but warm surface waters stratify. This creates distinct layers of water—warm on top, cold below—that make it more difficult for winds to mix high-oxygen surface waters with low-oxygen waters deeper down.

Because coral reefs are important sources of food and income for many people, they are often affected by human activities, such as fishing and tourism. Overfishing often removes herbivorous species from the reef. These species play a critical role in maintaining an ecological balance on the reef by grazing large algae that would otherwise overwhelm the reef. When they are removed in large numbers, no other animals take over the role of grazer, and algal growth can threaten the reef’s inhabitants.

Fishing, diving, and snorkeling can physically damage the reef. Anchors can damage coral skeletons, and careless divers and snorkelers can cause damage, albeit less severe, if their fins or oxygen tanks run up against the reef. Fishing gear can ensnare sections of the reef. Corals need years to fully recover from such damage, and that recovery may take longer if corals continue to be stressed by pollution or infectious disease from runoff.

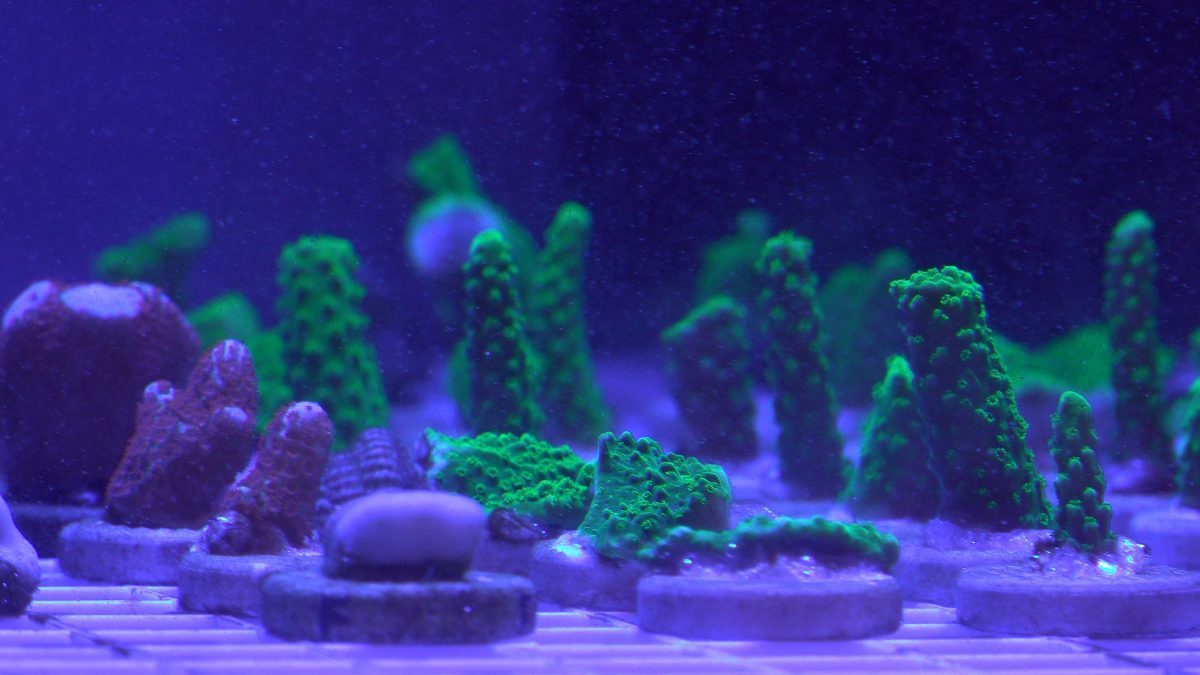

What is being done to help stressed corals?

Researchers are finding that some corals are more resilient to the onslaught of stressors, and microbial communities that inhabit these reefs may play a role in coral recovery and survival. Everyone can play a part in protecting these ecosystems. Reduce fertilizer and pesticide use—even if you live far from the coastline. Check that your sunscreen uses reef-safe chemicals. Clean up after your pets to prevent nutrients and pathogens from getting into our waterways. Properly clean up household chemicals to prevent them from polluting the water, and maintain septic tanks so they don’t flush pathogens into our coastlines during heavy storms. With effort, we can protect these essential ecosystems from permanent damage.

NOAA. How does climate change affect coral reefs? https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coralreef-climate.html

NOAA. How does land-based pollution threaten coral reefs? https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coral-pollution.html

NOAA. How does overfishing threaten coral reefs? https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/coral-overfishing.html

WHOI. How microbes reflect the health of coral reefs. https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/how-microbes-reflect-the-health-of-coral-reefs/

WHOI. Northern star coral study could help protect tropical corals. https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/northern-star-coral-study/

WHOI. Ocean acidification causing coral ‘osteoporosis’ on iconic reefs. August 27, 2020. https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/ocean-acidification-causing-coral-osteoporosis-on-iconic-reefs/

WHOI. What happens to marine life when oxygen is scarce? July 26, 2021. https://www.whoi.edu/press-room/news-release/what-happens-to-marine-life-when-oxygen-is-scarce/

News & Insights

Lab shutdowns enable speedier investigation of coral disease

Despite labs shutting down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, WHOI microbiologists are working fast to solve a different kind of outbreak—one travelling below the ocean’s surface and ravaging coral reefs from Florida to the Caribbean.

Shedding light on the deep, dark canyons of the Mid-Atlantic

WHOI biologist Tim Shank discusses the exploration of deep-sea canyons throughout the Mid-Atlantic Ocean and how ecosystems there can be managed sustainably in the face of climate change and increased human pressures.

Virgin Island Corals in Crisis

A coral disease outbreak that wiped out nearly 80% of stony corals between Florida’s Key Biscayne and Key West during the past two years appears to have spread to the U.S. Virgin Islands (U.S.V.I.), where reefs that were once vibrant and teeming with life are now left skeleton white in the disease’s wake.

News Releases

Ship-mounted camera systems increase protections for marine mammals

New funding will boost vital reef restoration work

[ ALL ]

WHOI in the News

eDNA methods give a real-time look at coral reef health

Harnessing the power of sound for coral reef restoration

Even ‘Twilight Zone’ Coral Reefs Aren’t Safe from Bleaching

[ ALL ]

From Oceanus Magazine

Five marine animals that call shipwrecks home

One man’s sunken ship is another fish’s home? Learn about five species that have evolved to thrive on sunken vessels

Counting on Corals

As struggling reefs put a squeeze on Belize’s Blue Economy, could heat-tolerant corals be the answer?

A cascade of life

The power of conservation, as seen through the lens of award-winning ocean photographer Henley Spiers

5 unlikely ocean friendships

How certain marine species keep each other safe, fed, and healthy through symbiosis

Can Sound Help Save Coral Reefs?

WHOI scientists use sound to attract larval corals that could help rebuild reef ecosystems

Dating Corals, Knowing the Ocean

Dating Corals, Knowing the Ocean  Deep-sea Corals

Deep-sea Corals  Reef Ecosystems

Reef Ecosystems  Reef Fish

Reef Fish