September 16, 2011Sun! It’s actually shining; skies are blue, seas flat, nary a whitecap in sight, and the “Weather Decks Secured” signs (which mean “stay off”) have been removed from the doors. The infernal rolling has largely ceased. The temperature soared to 10° C (50° F), wind ten—ten—knots. We could hardly believe it. People were walking around the decks in tee shirts, sun bathing in Dan’s backyard hammock. This weather’s supposed to hold for three whole days before the next inevitable low sweeps in.

We talked the other day about the bridge, the captain, and the mate’s spheres of responsibility. Now let’s go down one deck, via the “ladder,” as stairs are called in nautical lingo, and work our way deck by deck to, finally, the engine room. The Captain’s cabin and the chief scientist’s cabin share the 03 deck with the Shipboard Science Support Group (SSSG). Catie and Anton, heroes of the recent CTD incident, are responsible for everything electronic that collects science-related data—shipboard and lowered ADCPs, the multi-beam sonar for mapping bottom topography (bathymetry), satellite communications, CTD sensors, computer servers. They serve as the bridge between the scientists and the permanent shipboard equipment while underway and before then, deciding what the on-coming scientists will need. That seems a lot for two people, but they pull it off, though for them this trip may be little more stressful than usual.

On the 02 deck, one down, from forward to aft, we have the emergency generator room, science cabins port and starboard where crew and some of the science staff berth, the radio room, library, and the so-called upper lab, now commandeered by those pesky outreach people. The radio room is home to Tony, the Communications Electronic Technician. (“com-ee-tee”) It’s literally home; his cabin adjoins his office. You can always spot Tony; he wears shorts and tee shirts north of the Arctic Circle. He got his start at sea in 1980 when ships and shore were still communicating by Morse code and his digs would have been called the radio shack. Those days are gone, and now he maintains the bridge electronics, including the GPS systems, radars, gyrocompasses, fathometers, anemometers, and the complex dynamic positioning system. And if he needs to communicate with shore, any shore, he picks up the telephone. And this brings us down another level to the main deck. That is to say, it’s the lowest deck that stretches the entire length of the ship and is, therefore, usually the deck closest to the waterline. Up forward in its traditional position near the point of the bow, the “forepeak,” is the Bosun’s locker. Kyle’s domain is a storage room for about everything—paints, rope of all sizes, shackles, chain, and all manner of hardware. When not in use, the anchor chain, with hundred-pound links, lies below this locker, runs up through a huge hawse pipe to the anchor itself mounted near the bow.

Formally, the word is “boatswain,” but no one says that now, if they ever did. Now it’s bosun (the Skip calls him “swain.”). The bosun is in charge of the deck and all activity that happens thereon. By the traditional cliché, the bosun, a jack-of-all-trades, is a big, tough, salty guy, not to be trifled with. When I first came aboard Knorr two trips ago, in Reykjavik, Kyle was first man I met. I thought, now, here is the very model of a bosun, straight from central casting. Well, he turned out to be a kind, gentle figure, the personification of the nautical work ethic, still not to be trifled with, especially if you don’t subscribe to that ethic. He oversees the OSs and Abs, (Jose, Paul, Kevin, Wayne, and Sasha) who maintain the decks, houses, and all deck machinery. The movie lounge is aft of the Bosun’s locker—showings nightly at 1800. And that brings us to the most important spaces on the ship, the galley and mess room. Bobbie is Chief Steward, India is Cook, and Tony is the Messman. On this thirty-day cruise, Bobbie and India will prepare some 1,500 individual meals. For every lunch and dinner, they offer a meat or fish course of exceptional quality with dessert and freshly baked breads, muffins and coffee cakes for breakfast. Everybody’s talking about the quality of the food. The galley staff put in ten-hour days, but Bobbie and India take turns cooking lunch and dinner. Bobbie, who’s been cooking at sea for over thirty years, the last twelve on research vessels, is also responsible for ordering all the stores before the trips and also for all the housekeeping items, everything from cleaning items to bedding, towels, pillows, napkins, and utensils.

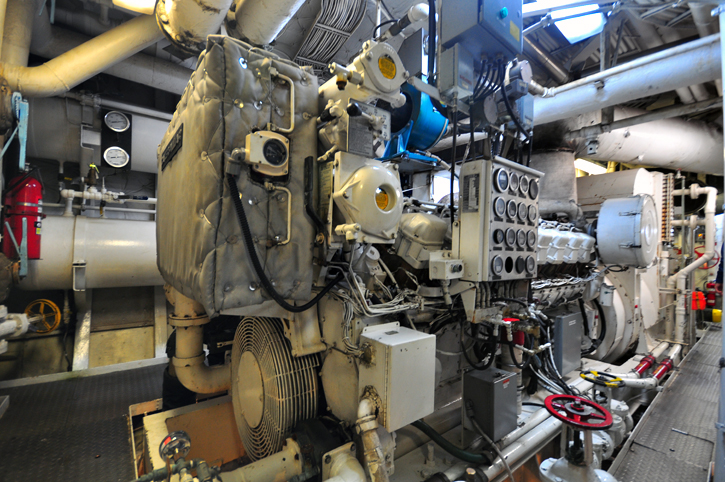

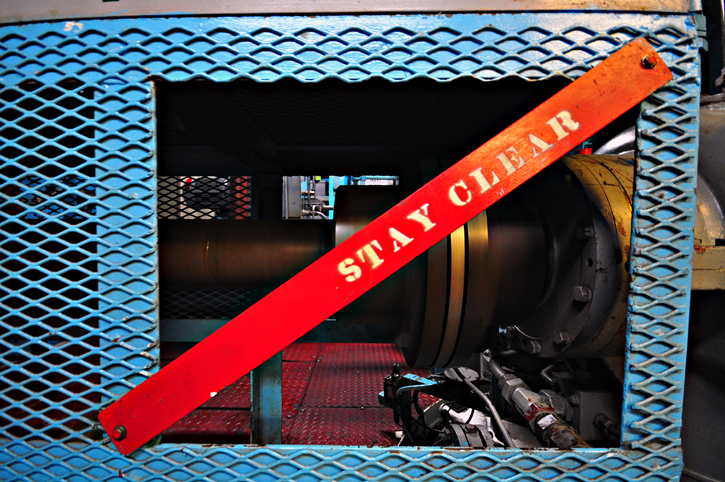

Aft of the mess, the main deck is devoted to lab space, and aft of the main lab the stern is flat and open, the work platform for launching all manner of instruments, from moorings to bottom-coring equipment. The two decks below the main are called platforms for some reason. Most of the first platform is devoted to crew and science berthing. Carnival Line customers wouldn’t be happy with the cabins (or the absence of alcohol), but they are perfectly adequate, comfortable, with bunk beds, plenty of stowage for personal gear and adjoining heads and showers. There is a laundry room, a gym, and another lab space on the first platform. Below that, on the second platform, we find the muscle of the ship—the engine room. Knorr has four Diesel electric engines, three with sixteen cylinders, each producing 1,500 horsepower, and one eight cylinder engine, “three cats and a kitten,” as they like to say. To reduce fuel consumption, only two engines run at a time under usual working conditions. Unlike most ships that transit from point to point at full Diesel-power speed, Knorr’s missions don’t require sustained high speed. The Diesels don’t directly drive the propellers—electrical motors do that, and the Diesels produce just enough power to keep the electric motors running. Almost everything on the ship—ovens, water pumps, heaters, navigation and lab equipment, etc.—runs on electrical power, and because of the nature of her work, priority goes first to maintain all these things, the so-called “house load,” and secondarily to propulsion.

Engineers, then, are comparable to your local utility companies packaged into a convenient eight-person department. “Captain” of department, Pete has three mates, but they’re called Assistant Engineers, first, second, third. (See “Engine Room Tour,” in Multimedia/Videos.) They stand fixed watches, manning the engine room day and night, and like the Skip’s mates, they have particular responsibilities. The First is in charge of the main engines, thrusters, pumps, hydraulic equipment, air conditioning and refrigeration. Todd, the Second Assistant, in addition to his engine room watch, is responsible for fuel and fueling (they burn the oldest fuel first) and the water makers (the desalinators can make 5,000 gallons of freshwater per day from seawater, but when in proximity to land, they stop making water for fear of loading polluted water.) Joe, the Third, is the plumber for the sanitation and sewerage systems, and he’s responsible for the portable fire-fighting equipment. There are also three Oilers, Nick, Ben, and Roger, who are comparable to the seamen working for Kyle. You see the oilers making rounds constantly checking this and that. Last but not least, there is Russ, the electrician, a one-man department. He’s associated with the engineering department, but mainly he’s off on his own attending to anything electric that doesn’t fall into Tony’s department or the SSSG’s. Yesterday one of the ice lights, like headlights mounted on the bow tower, packed it in. Kyle, Jen, and Russ lowered the tower only to find that they lacked the necessary replacement part. This is no big deal for our trip, but next trip they’ll be going to icy northern Greenland. So Russ managed to jury-rig something that will suffice, if needed, until they pick up the necessary part being shipped from Norway to Isafjordour. “Without Russ,” said Pete, “it would be like missing an arm.”

Most people never go down to the engine room, never even think of doing so. The engine room is sort of taken for granted. This, as Chiefski says, is a good thing. It means everything is working fine. However, it’s also a good thing if, when we turn on our cabin lights, take a shower, or even eat a hot meal, we recognize that it isn’t the same as doing so on land and it isn’t magic. It’s because these guys are doing their job down there. But I think the central point of all this is the self-sufficiency that could only result from all these departments first doing their individual work and then working together. That could be said about most all sea-going ships. However, unlike most ships, Knorr goes to the ends of the Earth, to places where you can’t visit the local marine-supply store to get what you need. You have to plan ahead, carry a lot of spares, and if something breaks, you’ve got to fix it yourself.

Last updated: December 27, 2011 | ||||||||||||

Copyright ©2007 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, All Rights Reserved, Privacy Policy. | ||||||||||||

Catie in the ship's technician office. © Rachel Fletcher

Catie in the ship's technician office. © Rachel Fletcher Russ, the Electrician. © Rachel Fletcher

Russ, the Electrician. © Rachel Fletcher Wayne and Kyle in the Bosun's locker. © Rachel Fletcher

Wayne and Kyle in the Bosun's locker. © Rachel Fletcher TV lounge and access to the bow thrusters. © Rachel Fletcher

TV lounge and access to the bow thrusters. © Rachel Fletcher One of the big engines. © Rachel Fletcher

One of the big engines. © Rachel Fletcher The propeller shaft. © Rachel Fletcher

The propeller shaft. © Rachel Fletcher