Sixty Years of Deep Ocean Research, Exploration, and Discovery with Human-Occupied Vehicle Alvin

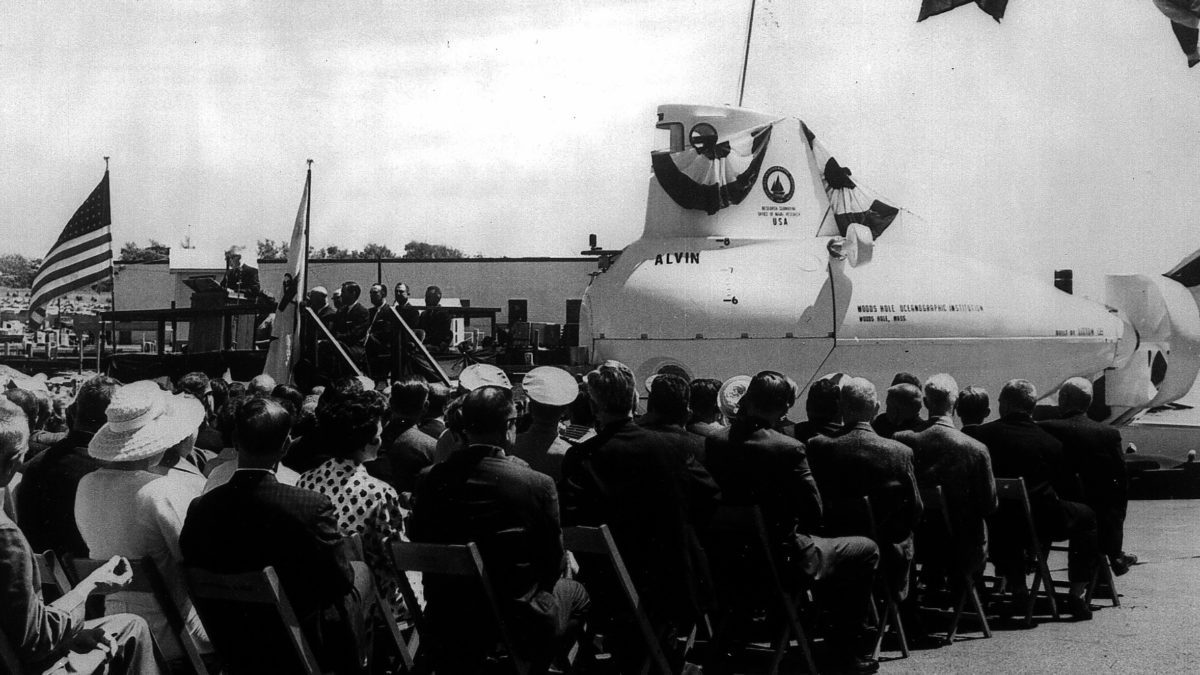

Alvin was commissioned on June 5, 1964, in a ceremony in the village of Woods Hole, Mass. On June 26, Alvin’s first pilot, Willaim Rainnie, took the sub on a tethered test dive off the WHOI dock. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Alvin was commissioned on June 5, 1964, in a ceremony in the village of Woods Hole, Mass. On June 26, Alvin’s first pilot, Willaim Rainnie, took the sub on a tethered test dive off the WHOI dock. (©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) June 4, 2024

In June 1964, the world’s first deep-diving submersible dedicated to scientific research was commissioned. What have we learned over the past 60 years?

Photos and video are available for use here.

Woods Hole, Mass. (June 5, 2024) — For 60 years, the human-occupied submersible Alvin has helped scientists expand human knowledge of the ocean and inspired countless individuals to learn more about its connection to our planet and to society. This year, the world’s most recognized and widely used deep submersible program celebrates six decades of safe, successful scientific study.

In its more than 5,200 dives, Alvin has provided over 3,000 researchers with unprecedented access to the deep ocean, enabling extensive observation as well as data and sample collection. It has supported publication of groundbreaking peer-reviewed scientific studies, enabled development of new tools to further oceanographic research, and has fostered the early careers of many scientists and engineers. Operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. Navy via its Office of Naval Research, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Alvin is the only publicly funded human-occupied vehicle available to the U.S. scientific community for exploring the upper Hadal region in-person.

Swimmers tend to HOV Alvin at the surface during a series of dives in Bermuda with its support ship R/V Atlantis in the background. (05/03/2018, Luis Lamar, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

“For 60 years, the deep-submergence vehicle Alvin has unveiled the ocean’s mysteries for the scientific benefit of society as a whole,” said Chief of Naval Research Rear Adm. Kurt Rothenhaus. “The Office of Naval Research is proud of its history with Alvin and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and looks forward to future discoveries and innovations.”

“Alvin’s long and extraordinary history is a testament to the importance of ocean research and exploration,” Rothenhaus continued. “In its first 60 years, it has transformed our view of life, responded to national emergencies, and inspired us all. I look forward to the remarkable discoveries it will make in its next 60 years.”

The story of Alvin begins around 1956, when, at a meeting of more than 100 scientists to discuss how to study the ocean depth, WHOI scientist and engineer Allyn Vine suggested building a submersible. Vine was an early proponent of U.S investment in deep-sea exploration, and the suggestion promoted a resolution that the U.S develop crewed undersea vehicles. In 1962, General Mills was contracted to build a small research vessel capable of diving to 2,000 meters (6,000 feet), and soon after, the newly formed WHOI Deep Submergence Group began using the name Alvin, after Allyn Vine.

Historic Commissioning

Alvin was commissioned on June 5, 1964, in a ceremony in the village of Woods Hole, Mass. On June 26, Alvin’s first pilot, Willaim Rainnie, took the sub on a tethered test dive off the WHOI dock. On August 4, Alvin made its first free dive, to a depth of 35 feet.

The following year, the sub made a 2,290 meter (7,500 feet) dive, tethered and unoccupied, to obtain Navy safety certification and pilot William Rannie made the first deep dives—to 1,097 meters (3,600 feet) and to 1,829 meters (6,000 feet).

Alvin’s Decades of Oceanographic Research and Exploration

Alvin’s first major undertaking was in response to an urgent request from the U.S. Navy in 1966 at the height of the Cold War. An Air Force B-52 bomber had collided with a KC-135 tanker over Spain, accidentally losing a hydrogen bomb that was on board to the depths of the Mediterranean Sea. A two-month search operating from a dock landing ship was successful and proved Alvin’s ability to conduct operations on the seafloor.

In 1973, Alvin’s steel personnel sphere was replaced with one made of titanium, extending its diving range to 4,500 meters (14,763 feet). This improvement enabled a 1974 joint U.S.-French expedition in which scientists were able for the first time in history to view a segment of Earth’s mid-ocean ridge in person.

Get to know Alvin, the deepest-diving human-occupied research submersible in the United States. Commissioned by the US Navy and operated by #WHOI since 1964, the iconic sub turns 60 this summer! (Video Produced By: Elise Hugus, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Hydrothermal Vents and the Titanic

Alvin’s investigations of seafloor hydrothermal systems in 1977 and 1979 and their associated ecosystems ushered in a new era of ocean exploration and research. The existence of organisms thriving on energy from chemicals in Earth’s crust rather than energy from the sun revolutionized views of where and how life can exist on Earth and elsewhere in the universe. In the following decades, Alvin discovered new seafloor environments that harbored other chemosynthetic communities, including investigations of hydrocarbon and saline seeps that also provide chemical-rich fluids supporting lush ecosystems far below the ocean surface.

But perhaps Alvin’s most well-known success is its exploration and documentation of the wreck of RMS Titanic. The wreck was first discovered at the bottom of the North Atlantic in 1985 by a team from WHOI and IFREMER (French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea), with a towed camera system. A year later, WHOI’s Robert Ballard and team dove to the Titanic, the first time humans had seen the luxury liner since it sank in 1912. Alvin deployed a prototype remotely operated vehicle (ROV), Jason Jr., which was able to penetrate the wreck and take stunning images of the sunken vessel.

Alvin also took part in a national response to the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster. The expedition examined deep-sea corals discovered seven miles from the wellhead. Alvin worked in tandem with the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), Sentry, to study the response of seafloor communities to oil exposure and laid the groundwork for long-term study of sites in the Gulf of Mexico.

In December 2010, after 4,664 dives, Alvin was taken out of service to undergo a major upgrade. A new, larger, titanium personnel sphere capable of reaching 6,500 meters (21,325 feet) and equipped with five, rather than three, viewports was integrated into Alvin’s modified frame. The upgraded Alvin was also equipped with fiber optic penetrators, a new command-and-control system, improved lighting and high-definition imaging, and increased data-logging capabilities, returning to service in 2014, picking up where it left off with studies in the Gulf of Mexico.

Human occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin arriving at the seafloor. (Photo by J. McDermott (Lehigh University); T. Barreyre (CNRS, Univ Brest); R. Parnell-Turner (Scripps Institution of Oceanography); D. Fornari (Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution); National Deep Submergence Facility, Alvin Group. Funding support from the National Science Foundation. © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 2024.)

The submersible underwent another round of upgrades beginning in 2020, building on improvements completed in 2014. A three-week sea trial in collaboration with the Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), which oversees the safety of all ships and submarines in the U.S. fleet, culminated in official certification to operate at depths to 6,500 meters, putting approximately 99% of the sea floor within reach. Researchers could now access the lower Abyssal Zone and the upper Hadal Zone—one of the least-understood parts of the deep sea and home to high-temperature hydrothermal vents, submarine volcanoes, subduction trenches, mineral resources, and more.

Since returning to service, Alvin helped discover pristine coral reefs off the Galapagos Marine Preserve, and recently found five new hydrothermal vents in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean using high resolution mapping from robots such as AUV Sentry to provide targets for Alvin and its dive team. This teamwork between deep sea robots is accelerating the pace of ocean discovery.

“Alvin continues to be the workhorse of deep-ocean research and exploration, remaining true to Allyn Vine’s vision of furthering knowledge about the ocean and the planet by enabling direct access to the deep seafloor,” said Anna Michel, chief scientist for the National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF). “There will always be a need for in-person exploration of the deep seafloor. Alvin offers the science community – including early career researchers - an unprecedented opportunity to visit a critically under-studied part of the planet.”

Where is Alvin now?

On average, Alvin conducts about 100 dives per year on missions to study the processes that create and shape Earth's crust, the chemical conditions that support life in extreme environments, and the vast diversity of life in the deep sea.

Currently, science teams from WHOI, UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and partner institutions are exploring the poorly understood deep-sea ecosystems at the Aleutian Margin off Alaska. The National Science Foundation and NOAA Ocean Exploration supported expedition will bring scientists to depths up to 5,000 meters (16,400 feet) marking the deepest dives in Alvin since its recent overhaul. In addition to Alvin, researchers will also use autonomous underwater vehicles Orpheus and Eurydice to map and explore known methane seeps sites along the Aleutian/Alaskan margin. The science team hopes by using these technologies in tandem to make the human-occupied Alvin dives more targeted and efficient.

“Alvin is an integral part of NSF’s support for oceanographic research by bringing researchers into the deep ocean to investigate important processes that are critical for society and the health of the planet,” said James McManus, Division Director, NSF Ocean Sciences. “The study of deep-sea ecology and life in extreme environments, submarine volcanic eruptions, underwater landslides, and the formation of valuable mineral deposits are just some examples of the ways Alvin enables important research. We look forward to many more decades of supporting this incredible submersible.”

Today, Alvin continues to contribute to the advancement of our understanding of the ocean. It has been a transformational building block for ocean engineering and research, continuing to make new discoveries and changing the way scientists explore the ocean. For 60 years it has taken scientists to places no human has ever been and enabled discoveries that have changed our understanding of life on our planet Earth, and beyond.

###

The Alvin Group is based at WHOI and supports all aspects of the sub’s operations, including maintaining and piloting the sub, integrating new scientific sensors and instruments for specific missions, and designing and building new parts and new tools to extend its capabilities. Alvin is part of the NSF-funded National Deep Submergence Facility at WHOI that also includes the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason and autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry.

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) is a private, non-profit organization on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, dedicated to marine research, engineering, and higher education. Established in 1930, its primary mission is to understand the ocean and its interaction with the Earth as a whole, and to communicate an understanding of the ocean’s role in the changing global environment. WHOI’s pioneering discoveries stem from an ideal combination of science and engineering—one that has made it one of the most trusted and technically advanced leaders in basic and applied ocean research and exploration anywhere. WHOI is known for its multidisciplinary approach, superior ship operations, and unparalleled deep-sea robotics capabilities. We play a leading role in ocean observation and operate the most extensive suite of data-gathering platforms in the world. Top scientists, engineers, and students collaborate on more than 800 concurrent projects worldwide—both above and below the waves—pushing the boundaries of knowledge and possibility. For more information, please visit www.whoi.edu