Research Highlights

Oceanus Magazine

Danielle Haas Freeman draws on the language of chemistry to solve an oil spill puzzle

News Releases

An international research team reports results of a three-year study of sediment samples collected offshore from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in a new paper published August 18, 2015, in the American Chemical Society’s journal, Environmental Science and Technology. The research aids in understanding what happens to Fukushima contaminants after they are buried on the seafloor off coastal Japan.

As temperatures rise, some of the carbon dioxide stored in Arctic permafrost meets an unexpected fate—burial at sea. As many as 2.2 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) per year are swept along by a single river system into Arctic Ocean sediment, according to a new study led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) researchers and published today in Nature. This process locks away the greenhouse gas and helps stabilize the earth’s CO2 levels over time, and it may help scientists better predict how natural carbon cycles will interplay with the surge of CO2 emissions due to human activities.

“The erosion of permafrost carbon is very significant,” says WHOI Associate Scientist Valier Galy, a co-author of the study. “Over thousands of years, this process is sequestering CO2 away from the atmosphere in a way that amounts to fairly large carbon stocks. If we can understand how this process works, we can predict how it will respond as the climate changes.”

Permafrost—the permanently frozen ground found in the Arctic and Antarctic and in some alpine regions—is known to hold billions of tons of organic material, including vast stores of CO2. Amid concerns about rising Arctic temperatures and their impact on permafrost, many researchers have directed their efforts to studying the permafrost carbon cycle—the processes through which the carbon circulates between the atmosphere, the soil and surface (the biosphere), and the sea. Yet how this cycle works and how it responds to the warming, changing climate remains poorly understood.

Galy and his colleagues from Durham University, the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, the NERC Radiocarbon Facility, Stockholm University, and the Universite Paris-Sud set out to characterize the carbon cycle in one particular piece of the Arctic landscape—northern Canada’s Mackenzie River, the largest river flowing into the Arctic Ocean from North America and that ocean’s greatest source of sediment. The researchers hypothesized that the Mackenzie’s muddy water might erode thawing permafrost along its path and wash that biosphere-derived material and the CO2 within it into the ocean, preventing the release of that CO2 into the atmosphere.

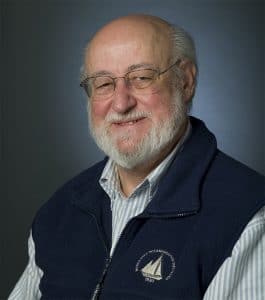

John W. Farrington of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) has been elected a fellow of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).Farrington, Dean emeritus and an emeritus member in the Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Department, is among 60 new fellows who will be honored for “exceptional scientific contributions and attained acknowledged eminence in the fields of Earth and space sciences.”

In 2009, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution embarked on a NASA-funded mission to the Mid-Cayman Rise in the Caribbean, in search of a type of deep-sea hot-spring or hydrothermal vent that they believed held clues to the search for life on other planets. They were looking for a site with a venting process that produces a lot of hydrogen because of the potential it holds for the chemical, or abiotic, creation of organic molecules like methane – possible precursors to the prebiotic compounds from which life on Earth emerged.

For more than a decade, the scientific community has postulated that in such an environment, methane and other organic compounds could be spontaneously produced by chemical reactions between hydrogen from the vent fluid and carbon dioxide (CO2). The theory made perfect sense, but showing that it happened in nature was challenging.

Now we know why: an analysis of the vent fluid chemistry proves that for some organic compounds, it doesn’t happen that way.

New research by geochemists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, published June 8 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is the first to show that methane formation does not occur during the relatively quick fluid circulation process, despite extraordinarily high hydrogen contents in the waters. While the methane in the Von Damm vent system they studied was produced through chemical reactions (abiotically), it was produced on geologic time scales deep beneath the seafloor and independent of the venting process. Their research further reveals that another organic abiotic compound is formed during the vent circulation process at adjacent lower temperature, higher pH vents, but reaction rates are too slow to completely reduce the carbon all the way to methane.

Humans concerned about climate change are working to find ways of capturing excess carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and sequestering it in the Earth. But Nature has its own methods for the removal and long-term storage of carbon, including the world’s river systems, which transport decaying organic material and eroded rock from land to the ocean.

While river transport of carbon to the ocean is not on a scale that will bail humans out of our CO2 problem, we don’t actually know how much carbon the world’s rivers routinely flush into the ocean – an important piece of the global carbon cycle.

But in a study published May 14 in the journal Nature, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) calculated the first direct estimate of how much and in what form organic carbon is exported to the ocean by rivers. The estimate will help modelers predict how the carbon export from global rivers may shift as Earth’s climate changes.