Research Highlights

Oceanus Magazine

Danielle Haas Freeman draws on the language of chemistry to solve an oil spill puzzle

News Releases

Humans concerned about climate change are working to find ways of capturing excess carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and sequestering it in the Earth. But Nature has its own methods for the removal and long-term storage of carbon, including the world’s river systems, which transport decaying organic material and eroded rock from land to the ocean.

While river transport of carbon to the ocean is not on a scale that will bail humans out of our CO2 problem, we don’t actually know how much carbon the world’s rivers routinely flush into the ocean – an important piece of the global carbon cycle.

But in a study published May 14 in the journal Nature, scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) calculated the first direct estimate of how much and in what form organic carbon is exported to the ocean by rivers. The estimate will help modelers predict how the carbon export from global rivers may shift as Earth’s climate changes.

Good management has brought the $559 million United States sea scallop fishery back from the brink of collapse over the past 20 years. However, its current fishery management plan does not account for longer-term environmental change like ocean warming and acidification that may affect the fishery in the future. A group of researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, and Ocean Conservancy hope to change that.

In a new study published April 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, scientists at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and their colleague from Rutgers University discovered a surprising new short-circuit to the biological pump. They found that sinking particles of stressed and dying phytoplankton release chemicals that have a jolting, steroid-like effect on marine bacteria feeding on the particles. The chemicals juice up the bacteria’s metabolism causing them to more rapidly convert organic carbon in the particles back into CO2 before they can sink to the deep ocean.

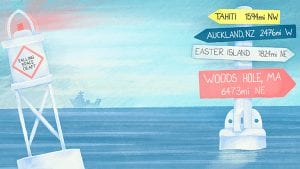

Scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) have for the first time detected the presence of small amounts of radioactivity from the 2011 Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident in a seawater sample from the shoreline of North America. The sample, which was collected on February 19 in Ucluelet, British Columbia, with the assistance of the Ucluelet Aquarium, contained trace amounts of cesium (Cs) -134 and -137, well below internationally established levels of concern to humans and marine life.

Four years after the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant accident, Japan is still recovering and rebuilding from the disaster. In March 2011 one of the largest earthquakes ever recorded shook Japan, creating a devastating tsunami and damaging the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant. The accident resulted in the largest unintentional release of radioactivity into the ocean in history.

On the fourth anniversary of the disaster, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and the Long Beach, CA-based Aquarium of the Pacific will debut a new program about ocean radioactivity motivated by the Fukushima nuclear accident. The program will be projected daily in the Aquarium’s Ocean Science Center on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Science on a Sphere® and will be made available to more than 100 institutions around the world through NOAA’s SOS Network with a capacity to reach over 50 million combined visitors.