Thomas Crook

Thomas Crook, an expert in undersea navigation at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who helped guide oceanographers to extraordinary seafloor finds, from the wreck of the Titanic to previously undiscovered clams, died June 5 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He was 67.

The cause was a stroke, said his wife, Mary Crook.

In the early1980s, engineers and scientists at WHOI began developing remote-controlled, deep-sea vehicles and robots designed to make maps, take samples of marine life, and explore and photograph mountain chains and volcanoes. Lacking street signs, the robots’ ship-based pilots, watching the undersea scene via on board video monitors, needed to figure out ways to maneuver their robots working miles below surface. This happened while scientists looked over their shoulders, directing measurements and sample collection.

Crook, who had joined WHOI in 1969 as a computer technician, became their guide. “You know how some people just have this instinct for directions when driving around town?” said WHOI biologist Stace Beaulieu in an Oceanus magazine article in 2008. “That’s what Tom has for navigating robots on the seafloor. He’s definitely the guy you want in the driver’s seat when you’re looking for things on the seafloor.”

Crook helped map the way by creating his own seafloor “guide posts,” using sound-transmitting instruments called transponders, still used today, that are sent overboard and anchored to the seafloor. The ship circles at the surface, receiving sound signals from the transponders, while it determines its own position using GPS. In such a way, the transponders’ positions in the ocean can be determined.

But to get the transponders to work well, researchers can’t just dump them over the ship’s rail. Slopes in the seafloor; being in the shadow of an underwater mountain; thick, mushy seafloor sediment—all these obstacles can interfere with sound transmission.

“Unless they are in the right places, they are useless,” said Dan Fornari, a marine geologist at WHOI. Crook had developed such skill for placing transponders that Fornari nicknamed him “Mr. Acoustics.”

Crook was born in New Bedford, Mass., on August 4, 1942. His father, Clarence, was a machinist who encouraged his three sons to pursue careers in science or engineering; they all did. He attended New Bedford Vocational High School and went on to graduate in 1962 from the New Bedford Institute of Technology (now the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth).

Crook worked as an electronics technician during four years in the Navy, then repaired and maintained computers for IBM in Boston. Months after joining WHOI, while working in a computer lab in Woods Hole, he met Mary Thompson. Within a year she became his wife.

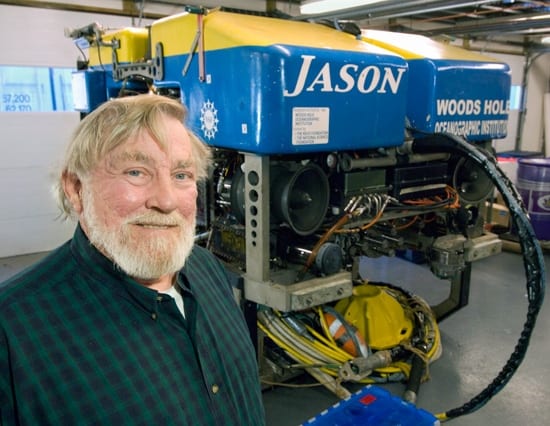

Crook—with his bushy beard, broad shoulders, and sometimes cantankerous nature— struck an imposing figure. Ship mates recall that he did not tolerate incompetence or frivolity. He was known to periodically sweep through ship laboratories reclaiming tools and computer parts that students had failed to return to him.

“We gained his acceptance by working hard in our own specialties and contributing to the practical aspects of the work: carrying boxes in the hot sun, sweeping the deck, and not whining when things got difficult,” said Dana Yoerger, a scientist at WHOI and a member of the Deep Submergence Laboratory, where Crook also worked.

He said Crook instructed through quiet example.

“No one taught us more than Tom. He taught us how to navigate, how to get along with the ship’s crew, and how to keep ourselves and the vehicles safe,” Yoerger said.

Crook sailed with scientists on hundreds of research expeditions worldwide, leaving ports in Africa, Europe, the Americas, and the Arctic. Though he was often away at sea for weeks and even months at a time, his wife said at home he rarely spoke of his shipboard contributions. Yet his expertise aided in the discovery of some of oceanography’s most celebrated finds.

On Sept. 1, 1985, he was on early morning watch aboard the research vessel Knorr when researchers solved one of the biggest maritime mysteries in modern history: the location of the wreck of the Titanic. At the time, researchers were using Argo, a 15-foot-long sled mounted with cameras and towed behind the ship.

“We called it ‘dope on a rope.’ Tom’s navigation skills were key to making it do what we wanted,” recalled Cathy Offinger, an operations manager with WHOI’s Deep Submergence Laboratory. She said that an hour after she had left her designated watch period, Crook navigated Argo to Titanic’s wreckage.

Four years later, in June 1989, Crook was part of the team that discovered the wreck of the German warship Bismarck, sunk off the west coast of France.

Scientists recalled how Crook worked patiently to reach improbable goals. Janet Voight, an expert on deep-sea life at The Field Museum in Chicago, credited Crook for helping her to locate an ocean-equivalent of a needle in a haystack: chunks of sunken wood colonized by tiny clams, which play a role in the base of the marine food chain.

Voight, working with Crook, positioned 17 mesh bags containing pieces of fir and elm more than a mile below the sea surface, to be used as a type of “clam bait.” Crook positioned transponders nearby. Twice in the next two years researchers returned with ships and undersea robots to collect the wood, using Crook’s original positioning of the transponders and the ship’s GPS to easily find the samples.

In the end, Voight described six species of clam that had made homes on her pieces of wood—all of them previously unknown. In a paper published November 2007 in the Journal of Molluscan Studies, she bestowed names on the new species. One, Xylopholas crooki, she named for Crook “in recognition of his years of service to science, specifically his superlative efforts during the 2002 cruise, the last before his retirement from WHOI, which allowed the deployments to be relocated and these species to be discovered.”

Told about the species named after him, Crook was characteristically modest, saying only that he “was surprised and honored.”

But Voight wouldn’t understate his role. “We literally would have been lost without him,” she said.

After Crook retired, he continued to work as a consultant with the Deep Submergence Laboratory. Offinger said he would come from his Monument Beach home to Woods Hole several times a month, usually on Tuesdays, when members of the lab had donuts.

He made a few more research expeditions at sea. “He was always looking at my schedule board, saying he was checking to see what was coming up so he could be sure navigation supplies were available,” Offinger said. “But I really think he was looking to sign up for one last adventure.”

In addition to his wife, Crook is survived by two daughters, Susan Crook of Pocasset and Teri Hathaway of Los Angeles; three sons, Michael Hathaway of Sunrise, Florida, Tommy Hathaway of Monument Beach, and Peter Hathaway of Brewster; two brothers, George Crook of New Bedford and James Crook of Norwell; and five grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his sister, Judith Laliberte.

Funeral services have been held. Donations in Crook’s honor may be made to the Upper Cape Technical School, att: Kevin Farr, 220 Sandwich Road, Bourne, MA 02532.